Martini – Defined, Explained and How to make

Words by Simon Difford

The Dry Martini, a blend of dry gin (or vodka) with a hint of dry vermouth and perhaps orange bitters is one of the quickest and simplest cocktails to make. However, due to the myriad of different ratios of these ingredients and the different techniques that can be employed to make it, let alone the garnish options, The Dry Martini is at the same time perhaps the most complicated of cocktails.

Martinis should be bespoke to the drinker

How people prefer their martinis is as personal as how they like their steak and with what sauce, so as you would if you were cooking a steak when making a Dry Martini for somebody else be sure to ask how they'd like it. Broadly speaking the options are:

- Method: Shake, stir or naked/direct.

- Base: Vodka or gin.

- Ratio: Anything from equal parts spirit to vermouth to 15:1.

- Seasoning: Optionally add dashes of orange bitters or even a splash of brine.

- Garnish: olive, lemon zest twist, onion, caperberry etc.

The combination of the numerous choices above mean there are potentially thousands of different ways to serve this seemingly simple cocktail. Despite the protestations of some very opinionated bartenders none of these options are right or wrong, it's down to personal taste. However, let's look at each in detail:

Shaken or stirred

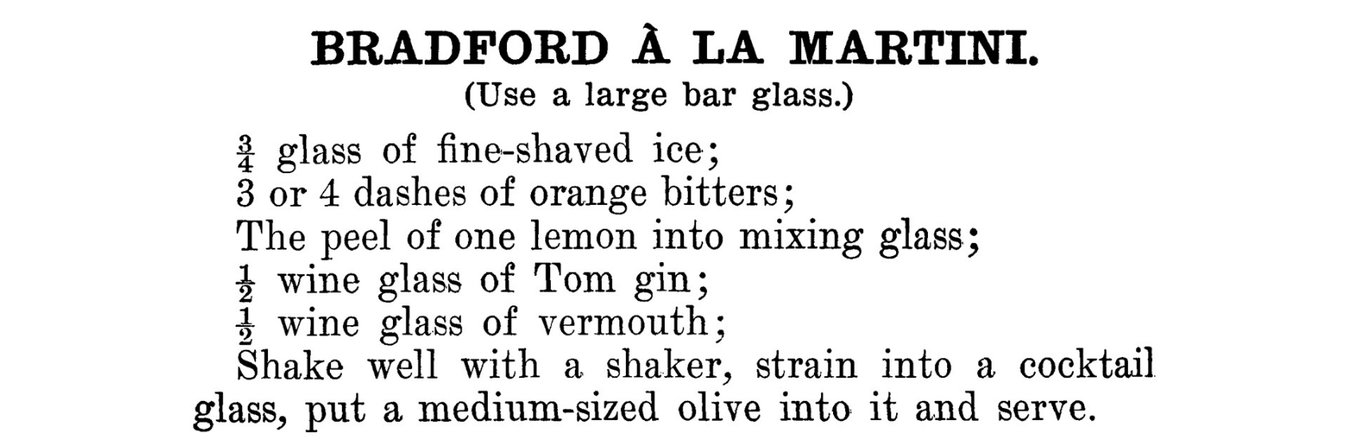

There is some debate, often heated, as to whether a Martini should be shaken or stirred. In Harry Johnson's 1900 edition of his Bartender's Manual he includes two Martini recipes - one simply titled "Martini Cocktail" and the other "Bradford à la Martini" - crucially the Martini is stirred while the Bradford is shaken. Hence, this precedent has led to cocktail lore stating that if a Martini is shaken it becomes a 'Bradford'. Although, Johnson's shaken Bradford recipe confusingly also includes "The peel of one lemon into mixing glass."

Bradford à la Martini in Harry Johnson's 1900 Bartender's Manual

The 1920s saw two books articulate the debate between shakers and stirrers - Harry McElhone's ABC of Mixing Cocktails and Robert Vermeire's Cocktails: How to Mix Them, and then in the 1940s the Stork Club Bar Book stating that the only "real difference is in appearance" and bartenders should "prefer to stir but certainly oblige a customer if they wished shaken". Then David Embury's 1948 Fine Art of Mixing Drinks advocates stirring to shaking for all liquor-based drinks.

English novelist W. Somerset Maugham is often quoted as saying, "Martinis should always be stirred, not shaken, so that the molecules lie sensuously one on top of the other." [Although I've not been able to find when and where he said this.]

However, it is another English novelist, Ian Fleming who has made shaken Martinis not just acceptable, but fashionable. The "Shaken, not stirred" catchphrase of his fictional British Secret Service agent, James Bond has ensured both the cocktail, and its two preparation options have remained high in the public consciousness for generations.

The "Shaken, not stirred" phrase first appears in Fleming's 1956 Diamonds Are Forever novel and continued in subsequent books and the films thereafter. Bond's immortal ability to return every few years in ever bigger blockbusters has kept his shaken preference in the public conciseness.

Strictly speaking, Bond, doesn't drink shaken Martinis, he drinks Vespers and it is theorized that Fleming knew that shaking Martinis was not good form - not gentlemanly and that it helped show that his daring character could get away with anything. After all, he had a license to kill!

U.S. President Richard Nixon is also said to have preferred his Martinis shaken, specifying what's known as an In and Out Martini, made by first shaking vermouth with ice and straining to discard vermouth, then adding gin to the now vermouth covered ice and shaker, and shaking again. [This method actually works very well when stirring a Martini.]

If, like Bond, you like your Martinis shaken, then don't let folk spouting off about "bruising the gin" put you off. Shaking makes for a colder and more dilute Martini with a softer mouthfeel due to the vigorous mixing introducing air bubbles into the drink. Sadly, these air bubbles also negatively affect the appearance, making the drink appear cloudy. It should be noted that shaking also increases the perception of vermouth in a Martini - see below.

Despite James Bond's protestations, current bartending convention is for Martinis to be stirred rather than shaken, so much so that if you prefer your Martini shaken then you're best advised to ask for a Bradford - at least that way you're sure to avoid someone spouting off that a Martini should never be shaken.

The "naked" or "direct" method

The key to a good Dry Martini is the temperature it is served at. The colder the better (although liquid nitrogen is taking things too far). Hence, it's advisable to store your gin or vodka in the freezer along with your serving glasses, while your vermouth should be in the refrigerator. If stirring, then also keep your stirring glass in the freezer.

Given the above, it is perhaps not surprising that a way of making Martinis emerged without the need to shake or stir at all. The merest hint of vermouth is either spayed as a mist onto the inside surface of a frozen glass using an atomizer, or a splash simply poured in, swirled around and the excess shaken out, usually onto the floor. Then frozen gin, or vodka, is simply poured directly into the vermouth-coated glass. This style of Martini is known as a "Naked Martini" or a "Direct Martini" and it originated at London's Duke's Hotel where it is still deployed, sometimes with devastating effect.

Base spirit

In his 1958 re-edition of his seminal The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks, David Embury writes, "There are people who like Vodka Martinis but, unless you use much more vermouth than I recommend, you will have nothing but raw alcohol with a faint herb flavor from the vermouth. The all-persuasive juniper flavor of the gin is entirely absent."

OK, so Embury is firmly in the gin camp when it comes to a Martini, but the simplicity and purity of a well-made Vodka Martini is a wonderful experience. And a stirred Vodka Martini without even a mist of vermouth is a great way to fully appreciate a good vodka. Also try going the other way with a Malty Martini - with jenever and dry vermouth.

Ratio of spirit to vermouth

I might be stating the bleeding obvious, but to avoid doubt, the less vermouth used in a Martini, the drier it is considered to be.

To briefly sum up the Martini's history, it was originally made with equal parts sweet vermouth and gin (old tom gin) and became drier with both the introduction of dry vermouth to America by Martini & Rossi and the introduction of London dry gin. The cocktail then progressively became even drier and more spirituous as the ratio of vermouth to gin fell to the extent that some omit it altogether. Fashion is a fickle thing, so as the Martini had become as dry as it could go, a trend is now emerging for more vermouth to be used.

As mentioned above, shaking appears to amplify the perceived ratio of vermouth in a Martini when compared to a stirred Martini with exactly the same ratio of spirit to vermouth. Hence, I'd recommend always stirring when a generous amount of vermouth is used, but perhaps shaking a Martini with a ratio such as 15:1.

The common Martini ratios, the accompanying terms, and suggested recipes, see Dry Martini Ratios

Seasoning

The earliest Martini recipes were a mix of gin and vermouth, but they also called for dashes of curaçao and orange bitters. While curaçao has disappeared from the now Dry Martini, the use of bitters has endured, particularly in high-end bars.

Inevitably, some folk like to take something as clean and cleansing as a Martini and make it "Dirty" with the addition of olive brine. The success of Dirty Martinis lies in what olive brine you use, and with this in mind, perhaps consider using Dirty Sue or Free Brothers Brine.

The gap between kitchen and bar has narrowed over recent decades, and with this interaction, so the practice of seasoning cocktails with a pinch of salt or a dash or two of saline solution has emerged. The Martini has not escaped.

Garnish

Some of the earliest derivations of the Martini have the now default garnish of an olive and/or lemon peel. In his 1891 recipe for a Martini, William Thomas Boothby called for it to be stirred with a lemon twist, then discarded. Also published that year, Henry J. Wehmann's Bartenders Guide, the second known recipe for a "Martini" gives the instruction, "Stir well with a spoon, strain into cocktail glass, squeeze a piece of lemon peel on top, and serve."

Then in 1895, the cherry emerged as a short-lived choice of garnish, being called for in G. F. Lawlor's The mixocologist and George J. Kappeler's Modern American Drinks. But just two years later, the Centralia Enterprise and Tribune from December 4th, 1897, reported this trend was over as part of an article on "new things in tipples": "Cocktails no longer contain a cherry at the bottom... grillrooms now serve cocktail olives."

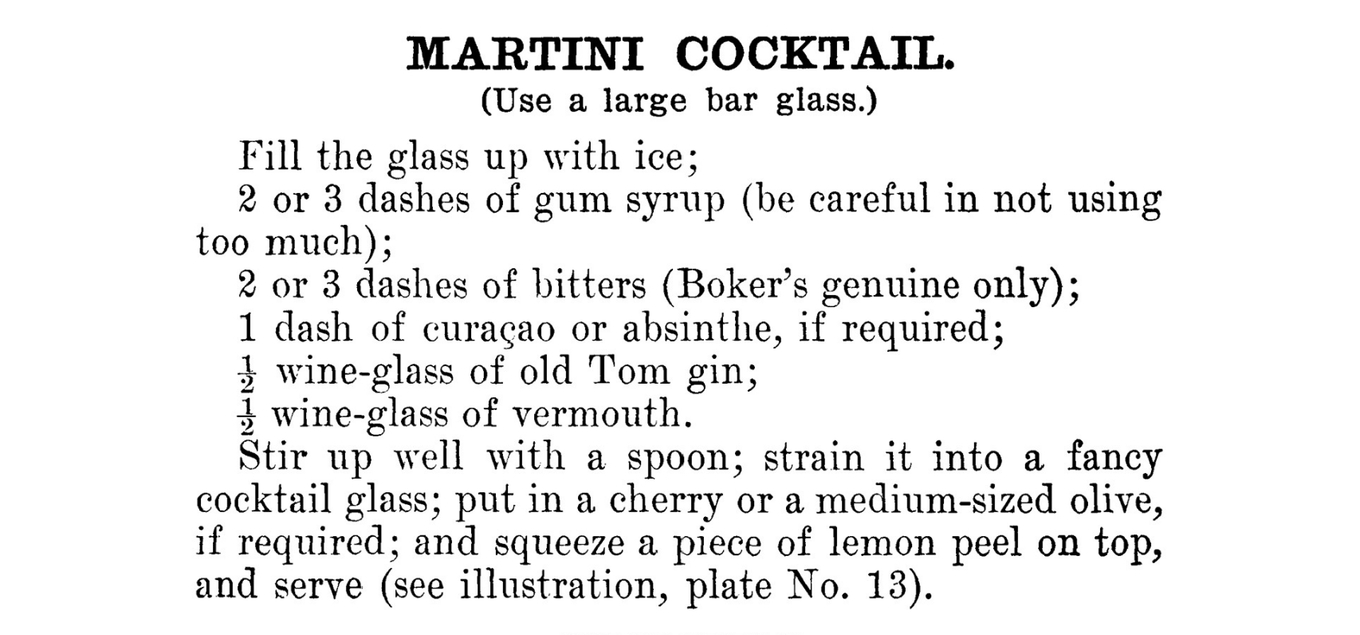

Harry Johnson's 1900 Martini Cocktail recipe includes the instruction, "put a cherry or a medium-sized olive, if required, and squeeze a lemon peel on top, and serve."

Martini in Harry Johnson's 1900 Bartender's Manual

By 1904, Frank P Newman's "Dry Martini Cocktail" in his American-Bar Recettes des Boissons Anglaises et Américaine gives the choice of serving with a lemon twist, a cherry or an olive, according to the consumer's preference.

1904 American-Bar Recettes des Boissons Anglaises et Américaine

1906 Louis' Mixed Drinks suggests a twist of lemon peel, while the 1912 Hoffman House Bartender's Guide says "put in a cherry or olive, and serve after squeezing lemon peel on top."

1912 Hoffman House Bartender's Guide

So a myriad of different garnishes - mainly centring around lemon zests or olives, and the number or combination of each have emerged for the Martini. Rather than expressing the oils of a mere citrus zest twist, some bartenders are floating essential oil on their Martinis.

Specific garnish specifications have led to Dry Martini variations being named after their specified garnishes. Whatever garnish you use, be sure it's cold. Or to quote Dale DeGroff, "it will be like adding a heat bomb to your drink."

Gibson = with two onions

Bohemian Martini = with a caperberry

Dickens Martini = without any garnish (i.e. no olive or twist)

Franklin Dry Martini = with two olives

Gin Salad Martini = with 3 olives and 2 cocktails onions

Hearst Martini - a sweet martini with orange and Angostura bitters and garnished with an orange zest twist.

Roosevelt Martini - with two olives

Tenner Martini - with grapefruit bitters and a grapefruit twist

Served straight-up, on-the-rocks or frappé

In his 1900 Bartender's Guide, Harry Johnson handily adds to his Martini Cocktail recipe the instruction to "see illustration plate No.13". This illustration appears later in the book, on page 205, and causes two areas of discussion. Firstly, the illustration is labelled "Martine Cocktail"[sic], which some conspiracy theorists say is more than a simple spelling mistake. More relevant is that the illustration depicts a tumbler-shaped glass filled with crushed ice next to a cocktail glass containing a drink served straight-up. Does this suggest that the Martini may also be served Frappé?

Plate No.13 from Harry Johnson's 1900 Bartender's Guide

Tom Daly's 1903 Bartender's Encyclopedia would appear to corroborate this under the recipe for a Cocktail Frappe with the instruction, "Manhattan and Martini Cocktail should be made the same way, except using orange bitters."

So the Martini might have once been served Frappé. I've personally witnessed it being ordered and served on-the-rocks. If you're the person who's going to drink it, then it really doesn't matter how you make and serve your Martini, as long as it's the way you like it. And if you're making a Martini for somebody else, please do them the courtesy of asking them how they'd like it rather than telling them how you think they should like it.