History of gin (1728 - 1794) - London's gin craze

Words by Simon Difford

The impact of gin on London's deprived inner-city population unused to anything stronger than beer has been compared to the effects of crack cocaine on modern day American inner-city ghettos. The period during which gin had its greatest impact in Britain has since become known as the 'Gin Craze'.

Today we use the term 'drug crazed' but back in 18th century London the poor were 'gin crazed'. This period is generally perceived to have been 1720 to 1751 but the truth is that these were the dates between which people publicly expressed their concern over the craze.

Daniel Defoe must have regretted his support of the Company of Distillers [see 1726], just two years after writing their pamphlet he publicly blamed gin for most of London's problems. In 1728 he wrote, "in less than an Age, we may expect a fine Spindle-shank'd Generation".

London's gin consumption peaked in 1743 and despite the Gin Act of 1751 these high levels lasted until 1757 when a series of crop failures forced distillation of grain to be banned.

Gin allowed the 18th century poor to forget the squalor and hardship in which they lived. It was a powerful drug that was cheaply and easily available. A much quoted gin shop sign from Tobias Smollett's 'History of England' reads, "Drink for a penny, dead drunk for two pence, clean straw for nothing."

Street vendors peddled cheap gin from carts and back street compounders used lethal ingredients such as turpentine and sulphuric acid to flavour their product. In the back rooms of gin shops, men and women spent the night unconscious on straw surrounded by the aroma of gin and vomit.

1723 to 1757 - Mother's Ruin

In 1723 the death rate in London outstripped the birth rate and it remained higher for the next decade with as many as 75% of babies died before they reached the age of five. Gin was also blamed for lowering fertility.

Women addicted to gin neglected their infants or quieted them with gin; babies were born deformed by foetal alcohol syndrome. Women more than men fell foul of gin so the spirit gained a famine identity and earned itself nicknames like 'Ladies' Delight', 'Mother Gin' or 'Madam Geneva'. The term, 'Mother's Ruin', survives to this day.

1726 - Boord Gin Founded

The London firm of Boord was founded in 1726. Over a century later this brand would become famous for its Old Tom gin and distinctive Cat & Barrel trademark.

1729 - The 1st Gin Act

The rising level of drunkenness among the poor and the shocking effects of poorly distilled gins in 1729 led the British Parliament to introduce the first of eight Gin Acts. These acts were given more official names and some were clauses inserted into other legislative acts, but they have become universally know as the 'Gin Acts'.

The 1729 Gin Act was intended to restrict gin sales by increasing duty on its sale and raising retail licensing fees. A major flaw in the act defines gin as spirits to which "juniper berries, or other fruit, spices or ingredients" had been added. Thus the act was circumvented by simply not adding these ingredients and the result was known as 'Parliamentary Brandy'.

Legitimate distillers were heavily penalised by this act while illicit distillers thrived. This first Gin Act was the start of a battle between those calling for temperance, the land owners, farmers and distillers, and successive government exchequers. Duty raised from gin helped fund the building of the British Empire.

1733 - The 2nd Gin Act

The ill conceived first Gin Act of 1729 failed to check the growth of gin and was repealed just four years after it became law. Its 1733 replacement sought to end sales of gin by street hawkers and general stores and encourage sales from taverns. The act was as flawed as the one it replaced and merely resulted in thousands of houses being turned into gin shops. This new act was the first to rely on professional informers for enforcement.

1734 - Judith Defour the killer

The affects of gin on those addicted to it where as profound as modern day hard drugs and anti-gin campaigners of the day in particularly latched onto the shocking case of Judith Defour as an example of its evil affects.

Judith, who worked twisting silk into thread, was the single mother of two year-old Mary and both lived in London's Bethnal Green Parish Workhouse. In January 1734 she collected Mary for a day out. The workhouse had dressed the child in new petticoats and Judith promised the warden to return the child by the afternoon that same day. Instead she turned up for work that evening a little worse for drink and with no sign of the child.

After continuing to drink gin at work, something that was not unusual, she told a colleague that she had left the child in the field. Mary was discovered dead and it transpired that Judith had strangled her with a handkerchief and stripped the child to sell its cloths to buy gin. She was tried and found guilty at The Old Bailey on 1st March 1734. The trading of her own child's life for gin greatly influenced the introduction of a further gin act.

1736 - The 3rd Gin Act

In 1736, the previous ineffectual 1733 Gin Act was replaced by a new Gin Act, officially named, 'The Act for Laying a Duty upon the Retailers of Spirituous Liquors'. This practically prohibited gin sales by imposing a two gallon minimum unit of sale and swingeing duties of £1 per gallon.

It also required retailers to purchase a £50 annual license (then equivalent to 14 months' wages for a skilled craftsman) with heavy fines for the unlicensed sale of spirits.

Like the previous act of 1733 this new act relied heavily on professional informers. It succeeded in putting many of the more respectable retailers of gin out of business but the act merely forced the sale of gin, or spirituous substances purporting to be gin, underground and the bootleg spirits peddled in the streets blinded and killed many of those who drunk them.

The highest proportion of gin shops lay in the poverty stricken narrow lanes and alleys of East London. These were hard for the authorities to control as these shops were little more than a plain room within a house or behind a shop front. They served as makeshift meeting places from where it was common for prostitutes to operate. Infamous addresses included Crock Lane in Holborn, Rosemary Lane near Tower Hill and Hog Lane, while the main arterial routes in and out of The City such as Mile End Road, Kingsland Road and Whitechapel Road were lined with street vendors operating from small stalls.

1737 - The 4th Gin Act

The Gin Act of 1737 was not actually an act in its own right but a clause inserted into the so-called 'Sweets Act'. This served as a revision to the 1936 act in that it plugged the previous acts loophole allowing the gin trade to continue via back street gin shops and makeshift stalls. This new act also allowed informants of even the most petty of gin sellers to be rewarded.

The 1737 act led to a surge in informants and convictions. Thousands of Londoners were prosecuted for flouting the Gin Act - mostly women. Despite this, gin sales continued to rise. This Gin Act stoked a backlash against not only the Gin Act but also the rule of law and government itself.

1738 - The 5th Gin Act

Hardly a day passed without a gin informer being attacked or killed, sometimes by mobs of hundreds. Magistrates read the Riot Act but were ignored as the rabble hit out at both informers and authority.

The Gin Act of 1738 virtually outlawed gin and made attacks on informers a felony. It also dealt with the problem of excise officers refusing to arrest friends and neighbours by empowering individuals to arrest gin sellers. Gin distilling was forced further underground and illegal stills and drinking dens proliferated, particularly in London's unruly east.

1738 - Captain Dudley Bradstreet & old tom gin

Captain Dudley Bradstreet researched the intricacies of the Gin Act and took advantage of a loophole that said an informer must know the name of the person renting a property from which gin was illegally being sold for the justices to have the Authority to break into the premises in order to arrest the transgressors of the act.

In 1738, Dudley had an acquaintance rent a house in the City of London on Blue Anchor Alley and nailed a sign of a cat in the window, under its paw he concealed a lead pipe. He let it be known that gin would be available from a cat in the alley on the following day and moved in with supplies of food and £13 worth of gin purchased from Mr. Langdale's distillery in Holborn before barricading himself into the house.

His patrons pushed coins though a slot in the cat's mouth and Bradstreet would in return pour gin down the pipe to trickle out from under the cat's paw. Customers would hold a cup or simply their mouth under the paw to receive their gin. The authorities found themselves powerless to act and Bradstreet apparently profited from his scheme for three months before so many copied him that competition caused him to move on.

Years later, in 1755, Bradstreet wrote about his exploits in a book entitled 'The Life and Uncommon Adventures of Captain Dudley Bradstreet' (page 78). In this he described how he had overcome the Gin Act.

There is no evidence linking Bradstreet to the term 'old tom'. It is my belief that Bradstreet's cat and the term 'old tom' are coincidental and that 'old tom' originated in the 1830s in deference to the distiller Thomas Chamberlain (see 1830s). He did however, start the trend for what became known as Puss and Mew houses. Vendors would sit concealed within a premise and customers wanting to buy gin would say 'puss'. The vendor would respond with 'mew' and push out a drawer into which the customer would deposit payment. The vendor would recover the coins from the drawer and push it forward filled with a measure of gin. These human vending machines where found all over London and for a short period the subterfuge succeeded in stifling attempts to enforce the 1738 Gin Act.

1740 - Booth's Gin Established

The Booth family, who moved to London from north-east England, were established wine merchants as early as 1569. By 1740 they had added distilling to their already established brewing and wine interests and built a distillery at 55 Cowcross Street, Clerkenwell, London. This date is referenced on Booth's label and makes Booth's the oldest gin brand (not jenever brand) still in existence.

1740 - Finsbury gin established

The Finsbury name was founded by Joseph Bishop back in 1740 and is possibly a reference to Clerkenwell springs which was once the centre of London's gin industry and part of the Borough of Finsbury.

1743 - The 6th gin act

Attacks on informers continued despite the measures introduced in the 1738 Gin Act. Matters were made worse by corruption within Excise Office and crooked informers. Few of those convicted could pay the £10 fine but informers were still due their £5 reward. The Act was running at a huge loss and by 1739 the Commissioners had run out of money to pay informers.

Over the years the various Gin Acts had been in force, production of spirits had risen by over 30% to eight million gallons a year. Although the sale of gin was officially outlawed, consumption was equivalent to every man, women and child drinking two pints every week.

England was at the height of the War of Austrian Succession (1740-1748) and a New Act was sought to reduce gin consumption, settle public unrest and raise revenue for the war effort. The Gin Act of 1743 was the first to target distillers rather than retailers and it reduced the retail licence fee from £10 to just £1. This was a level that legitimate publicans could afford to pay so ending the career of informers. The 1743 Act also forbid distillers to sell gin direct to the public and increased the excise duty payable by them. However, because the level of duty was relatively low, the distillers did not revolt against paying it - they had little choice as there were relatively few of them, making this new act much easier for the authorities to enforce.

This was the first Gin Act to actually cause consumption of gin to drop.

1747 - The 7th gin act

The War of Austrian Succession (1740-1748) still raged causing a government funding crises. The response was the Gin Act of 1747 which increased the excise duty payable by the gin distillers but appeased them but allowing wholesale distillers to buy £50 licenses allowing them to sell directly to the public.

The increase in duty further dampened demand for gin and government reviews from the spirit fell. Beer tax was reduced in the hope of raising revenue from increased beer consumption so levels of insobriety changed little.

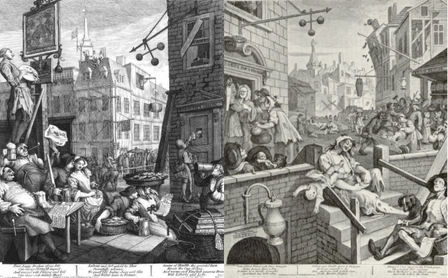

Beer Street and Gin Lane by William Hogarth

1750 - Hogarth's Gin Lane

Set in London's St. Giles area, where Centre Point stands today, William Hogarth's Gin Lane print depicts the excesses and resulting hardship brought about by gin consumption. This is juxtaposed by another, corresponding print tilted Beer Street which shows healthy and happy Londoners enjoying their ale. These works of propaganda are thought to have been commissioned by the magistrate Henry Fielding.

1751 - The 8th gin act

The end of the War of Austrian Succession in 1748 brought with it a new threat to London's society. Crime. The returning soldiers had no trade and were not given any support by the state so many simply started steeling and mugging. The 1750s saw the moral reformers blame the still growing crime wave on the excesses of gin and they used this as ammunition in their lobbying for prohibition.

In 1751, a Westminster magistrate, Henry Fielding, also a respected playwright and novelist, published a scare-mongering paper titled An Enquiry into the Causes of the Late Increase in Robbers. This links cheap gin with the rising crime wave and was timed to coincide with the start of the 1751 parliamentary session. It formed part of a well orchestrated lobby calling for gins prohibition.

Fortunately for the distillers, the Gin Act of 1751, known as the Tippling Act, which inevitably followed in the wake of the anti-gin crusade only modestly increased duties on distilled spirits. It doubled the price of a retail licence to £2 and specifically made that licence only available to inns, alehouses and taverns. The act also granted immunity from prosecution and a reward of £5 for any unlicensed retailer that informed upon a distiller supplying them.

Although the duty increase was small, the 1751 act practically ended all back street gin sales so dramatically affecting its availability. By 1752 the volume of spirits produced on which duty was paid had fallen by over a third.

1757 - English grain distilling banned

In 1757 the harvest failed and fearing a bread shortage, exports of corn and malt were banned, as was all distillation of wheat, barley, malt or any other grain. This was intended to be a temporary measure but when the 1758 harvest proved little better, the ban was extended.

Spirits were still being made from imported sugar molasses but due to the high cost, production was comparatively small, and so the spirits that were available were priced beyond the reach of the poor.

Sobriety prevailed and London enjoyed growing prosperity and many civil improvements to its infrastructure with the construction of new roads and the introduction of street lighting. London's standard of living rose for both rich and poor alike.

1760 - Grain distilling restored

The bountiful harvest of 1759 led distillers and farmers to lobby for distillation to be legalised. However, their demands were countered by those of moral reformers, a stronger church and the growing middle classes who argued for out-and-out prohibition.

However, the lack of availability of gin was causing rum imports to rise and this, along with the preference for the government to earn excise duty from domestic distillers led to a compromise. In March 1760, a bill restored corn distilling but with double the levels of previous excise duty. Britain's distillers also benefitted from the introduction of subsidies for all spirits exports.

The cost of getting drunk on spirits was now greater than that of getting drunk on beer so the urban poor simply returned to beer and by the 1760s a proliferation of dingy back street pubs had sprung up, most remaining open throughout the night. Meanwhile the more expensive gin found new respectability and regulation of distilling led to an improvement in quality and the growth of a handful of dominant distillers.

1761 - Greenall's gin established

Thomas Dakin built his gin distillery on Bridge Street in the Cheshire market town of Warrington in 1760, finally commissioning and producing his first gin in 1761. The Greenall family had been brewers in St Helens for some time when Edward Greenall bought the Dakin distillery in 1870. The 'G' & 'J' of the now familiar G&J Greenall comes from his two younger brothers, Gilbert and John. The company is now simply known as G&J Distillers.

1769 - Foundation of Gordon & Company

In 1769 Alexander Gordon established Gordon & Company in London's Bermondsey. He was born in Wapping, London but at the age of four, after his father's death, was brought up by his Grandfather in Glasgow, also Alexander.

As an adult he moved back to London and lived on Charterhouse Square, Clerkenwell where he moved his distilling operations from their original Bermondsey location in 1798 due to the superior quality of the Clerkenwell water available from the plentiful wells after which the area is named.

The establishment of Gordon & Company and the others which followed in the subsequent years heralds the start of a regulated and reputable English distilling industry which produced quality spirits. London was the centre of this industry, partly due to The River Thames and its docks and quays which supplied distillers with exotic raw ingredients such as oranges, lemons and spices from British colonies in the Caribbean. London was the world's largest city and its docks the busiest.

Towards the end of 1897, Reginald C. W. Curry, the then head of Gordon & Company was approached by Charles Waugh Tanqueray with a view to a merger. Accordingly, in 1898 the two companies merged to form Tanqueray Cordon & Company.

1770 - Burnett's White Satin established

It is claimed that Burnett's White Satin was first made in 1770 by the Lord Mayor of London and that the originator and Lord Mayor was Robert or Thomas Burnett: according to my research, neither a Robert nor a Thomas Burnett has ever held this office.

My understanding is that Robert Burnett joined the company that came to bear his name in 1770, established his gin, then became Sheriff of London in 1794 and was knighted the following year. There is a requirement for a Lord Mayor of London to have previously served as a Sheriff but Robert Burnett never went on to hold the mayoral office.

1777 - Canny Scots

The Haigs and Steins started exporting grain alcohol to London for rectification into gin in 1777. Much to the upset of the English distillers this was the start of a flow of cheap, quality grain alcohol from Scotland which has grown over the centuries to the extent that what little gin is still produced in London today is more often than not, made with Scottish grain alcohol. Formally London distilled brands such as Gordon's and Tanqueray are now made in Scotland and even Beefeater, still distilled in London, is bottled in Scotland.

1793 - Plymouth gin established

The Black Friars Distillery where Plymouth Gin is made was set up in 1793 when the Coates family joined the established distilling business of Fox & Williamson and converted the old Black Friars monastery.

The Coates family made a gin that was fuller-flavoured with less citrus and more pungent root flavours than its typical London dry counterparts. The Royal Navy purchased large quantities of gin for its officers (ratings were issued with rum, not gin) and as Plymouth was a naval dockyard much of Coates business was to the officers' mess. Other naval towns such as Bristol and Liverpool also had distilleries supplying the navy with the town's particular style of gin.

Plymouth gin is the only vintage gin brand to still be made at the same distillery in which it was created, but the Black Friars distillery has been owned by a range of different companies. It is said by some that when it was owned by Seager Evans, a company based in London's Deptford but controlled by Schanley of New York, the recipe was changed so the gin fell more in line with the predominant London Dry style and with American tastes. Present day Plymouth gin is certainly in the style of a London dry gin and conforms to all the legal criteria to be labelled as such.

1794 - London trade directory

A 1794 trade directory for the cities of London and Westminster and the Borough of Southwark lists over 40 distillers, malt distillers and rectifiers. This proves that gin production was a well-established industry in the city at the time.