Words by By Simon Difford (based on and with extracts from Schweppes The First 200 Years published 1983).

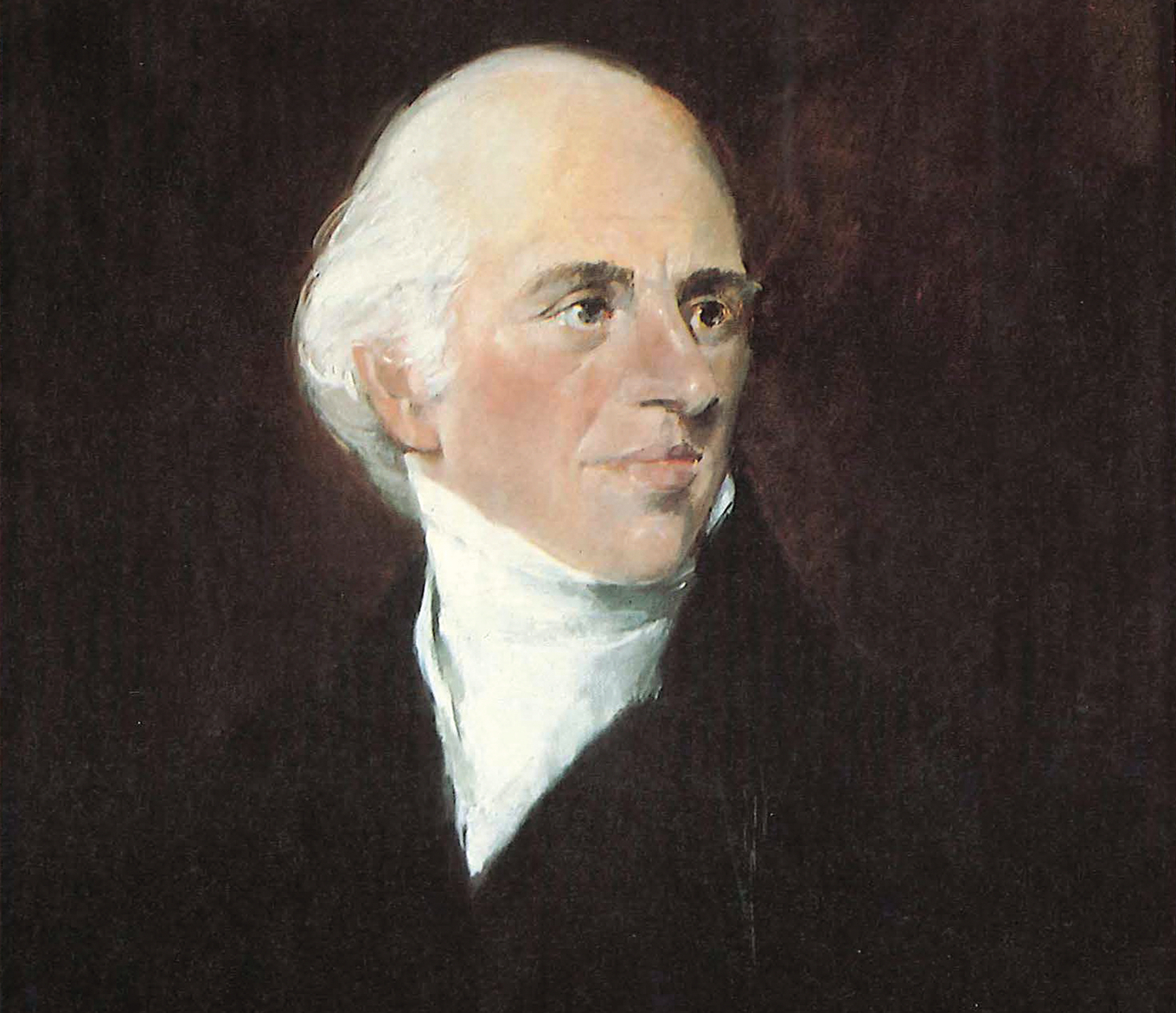

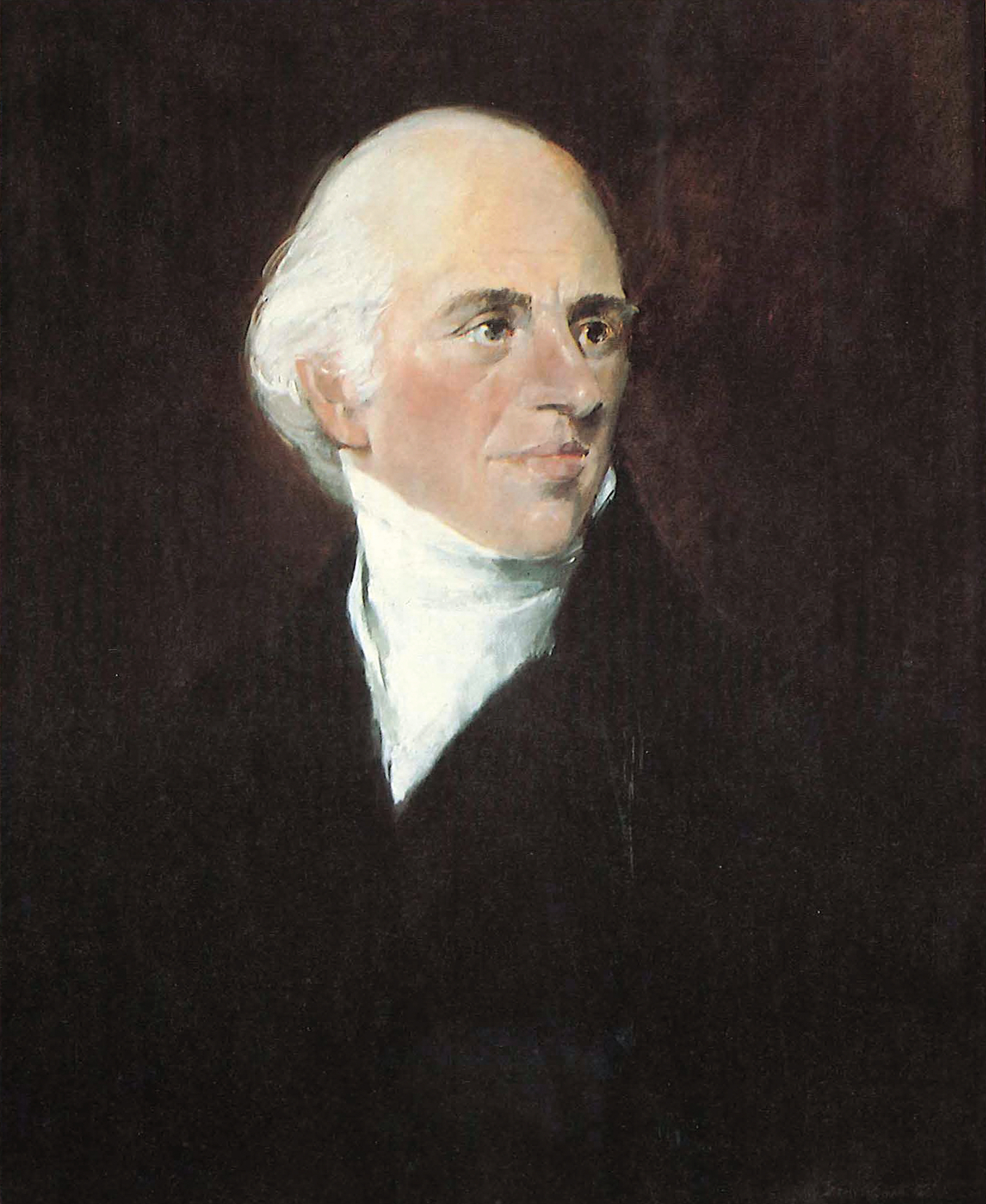

The world's carbonated soft drinks industry – from soda water through to cola, tonic water, ginger beer and the myriad of flavours and styles of fizzy pop now available – was established in the late 1700s by Jacob Schweppe, a jeweller living in Geneva, Switzerland.

It's a story of the popularity of bottled natural spa waters, leading to the commercial development of manufactured mineralised waters that drove a quest for carbonation. This led to the flavouring and sweetening of those waters, through ginger beer and tonic water to the modern-day range of products from Schweppes, the company Jacob Schweppe gave his name to.

The foundations

The Romans thought certain mineral waters beneficial to health and many of their spa towns proved popular with the gentry of the 18th and 19th centuries who flocked to the same towns to take the waters in the belief they would relieve digestive problems and other ills. A belief shared by doctors who prescribed waters from particular spa towns to cure specific complaints.

Naturally effervescent mineral water from towns such as Selters in the German Taunus mountains were thought to be particularly beneficial. Against this background it is easy to understand the desire to create manufactured waters with the mineral content of water from towns such Pyrmont, Spa and Rochelle, and to carbonate these bottled waters.

Joseph Priestly, an English clergyman and scientist, experimented with impregnating water with "fixed air", initially using carbon dioxide collected from vats of fermenting beer. He discovered the secrets of successful carbonation - the need to exclude atmospheric air, the benefit of saturating the water with CO2 by compressing the gas, and that absorption of the gas into the water was best achieved when under pressure when agitated. However, lacking the means to properly progress his experiments much of his conclusions remained theoretical.

Schweppe, a Swiss watchmaker and jeweller by trade, who had the financial means to peruse his hobby as an amateur scientist, picked up on work by Priestly and others when he started experimenting with mineralised and carbonated waters in 1767-8. After some four years work, in 1772, Schweppe published a pamphlet in London titled Directions for Impregnating Water with Fixed Air.

Pursuing his curiosity rather than any commercial opportunity, he gave up his full-time profession to concentrate on his quest to improve the carbonating apparatus he had developed to make "Medicated water". Rather than let the water he was producing go to waste he gave it free of charge to doctors in his town so they could supply their poorer patients.

As the quality of the sparkling water he produced improved, so did demand. He continued supplying people who asked for his Medicated water without charge, taking pleasure in the fact they valued the properties of the carbonated water he was giving them. However, many asked to pay, and as demand increased so he reluctantly started applying a nominal charge to cover his outgoings.

By 1783, or perhaps earlier, Schweppe had progressed from producing water as a by-product of his experimentations to commercial production. It is fair to say that Jacob Schweppe founded the world's soft drinks industry as he was the first to invent the equipment capable of carbonating water to a level that matched or exceeded natural mineral waters, and in the quantities necessary to make his water commercially viable.

As volumes grew, even extending to foreign customers, Schweppe entrusted the handling of sales to a friend. And not just sales, Schweppe had such confidence in this "friend" that he also showed him how to operate his machine so he could also assist in production. This trust proved misplaced.

The friend approached a noted engineer in Geneva, Nicolas Paul, to make a machine that would enable him to produce and sell his own carbonated water. Paul seized on the opportunity, deliberately producing a poorly functioning machine to sell, while also making a much better machine for himself. Paul then declared himself in competition with Schweppe.

Worried that competition from Paul would be detrimental to his fledgling business and recognising Paul's engineering skills and expertise in pump engineering, in April 1790 Schweppe formed a partnership with Nicolas Paul, a partnership which also included Nicolas' father Jaques Paul, equally as skilled an engineer as his son - although the father's contribution to the partnership proved short-lived as he died after a prolonged illness in 1796.

Nicolas Paul had long been friendly with Henry Albert Gosse, a highly respected pharmacist in Geneva who had also experimented with producing manufactured mineralised Medicated waters. The Schweppe partners thought the pharmacist's skills would be a valuable addition in their quest to mimic the mineral properties of various spa waters. The pharmacist's reputation also helped bolster their standing with the medical profession - an important part of their business. Thus, Gosse joined the partnership on 1st July 1790.

Over some eight years Schweppe had built a good business selling his Medicated waters which imitated natural waters from Seltzer and Spa. His waters were produced using non-distilled water, but with his new partners the offering was extended to also mimic waters from Pyrmont, Bussang, Courmayeur, Vals, Seidschutz, Balaruc and Pussy, all based on distilled mineral water.

As well as expanding and improving the range offered, the partners wanted to open new international markets, particularly London. It was decided that Jacob Schweppe would move to London to establish a new factory and develop sales. He left Geneva late in 1791, travelling through a hard winter to arrive in London on 9th January 1792. He quickly set up a factory at 141 Drury Lane, then a poor part of London.

Unlike Geneva, where Schweppe's waters were by far the market leader, in London there were already numerous apothecaries selling mineral waters made with rudimentary machines - some even mounted on horse-drawn wagons. The carbonation these achieved was very low compared to that produced by Schweppe's compression pump machine, but he struggled to compete against their already established trade.

By December 1792, Schweppe's partners back in Geneva wrote urging him to give up on London due to the expenses they were incurring. This led to a falling out between Schweppe and his colleagues. After arguments and the appointment of attorneys, on 20th February 1796, the partners in Geneva signed a joint declaration which said that to bring their dispute to an end they would consider their partnership agreement with Schweppe terminated. The basis of the settlement, which had been proposed by Schweppe, awarded the fledgling London business to Schweppe with the established Swiss business equally divided between the other partners.

Jacob Schweppe in England

From 1793 Schweppe was free to continue business in England unimpeded by his partners. By 1794 he had moved production to 8 King's Street, Holborn, then to 11 Margaret Street near Cavendish Square, a street where at several different addresses the company stayed until 1831.

Schweppe soon benefitted from recognition and recommendation by the medical profession. In October 1794, Matthew Bolton, the industrialist who made Watt's first steam engine, wrote to Dr Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles Darwin, "Mr J. Schweppe, preparer of Mineral Waters, is the person whom you have heard me speak of and who impregnates it so highly with flexible air to exceed Champagne and all other Bottled Liquors. He prepares it of 3 sorts. No.1 is for common drinking with your dinner, No.2 is for Nephritick [kidney disease] patients, and No.3 contains the most alkali and given only to more violent cases, but I know not the quantity of alkali in either. It is contained in Strong Stone Bottles and sold for 6s.6d per doz. Including the Bottles."

Soda water

Sometime in the mid-1790s, the term 'Soda Water' came into popular use, although such waters had existed under various names for some 30 years. "Soda water" first appeared in a Schweppe's advertisement in 1798.

That 1798 advertisement lists waters prepared and sold by Schweppe: Acidulous Soda Water in single, double and triple strengths; Acidulous Rochelle Salt Water in single or double strengths; Seltzer, Spa and Pyrmont Water; as well as Tooth Lotion of Soda.

Acidulous water was recommended for complaints of the kidney or bladder, the stone, acidity, indigestion and gout. Seltzer was also recommended for medical uses, and for its pleasant taste. It was described as a safe and cooling drink for "persons exhausted by much speaking, heated by dancing or when quitting hot rooms or crowded assemblies." The Rochelle Salt Water was sold as purgative [laxative] "not ungrateful to the palate".

Soda water during this period was carbonated water to which soda had been added due to its perceived medical benefits. However, today 'soda water' refers to a water charged with carbon dioxide, WITH OR WITHOUT any soda content. This transition took place in American as early as 1830 but did not occur in Europe until into the 1900s.

J. Schweppe & Company

In 1798, after successfully developing his business in England, and aged 58, Jacob Schweppe prepared for retirement by selling three-quarters of his company to three men from Jersey, retaining one-eighth share for himself and the other for his daughter, Colette.

Then in 1799, he completed his retirement by relinquishing half of his and his daughter's shares to Stephen DeMole in return for his undertaking to devote his time to looking after the business on behalf of Jacob and his daughter. He returned to Switzerland but travelled during his retirement. He died a wealthy, content old man aged 81 on 18th November 1821.

The new owners of Schweppes continued to build on the business started by Jacob, establishing a network of agents across the country. Strategically located regional factories were opened, the first being in Bristol in 1803, with products moved across the country by canal boats, coastal vessels and horse-drawn waggons (railways came thirty years later). By the 1820s, an export trade was also being developed.

The 1st June 1834 marks another turning point in the history of Schweppes, as this is when two new owners took over the business, John Kemp-Welch, a wine merchant and William Evill, a prosperous silversmith, both from Bath.

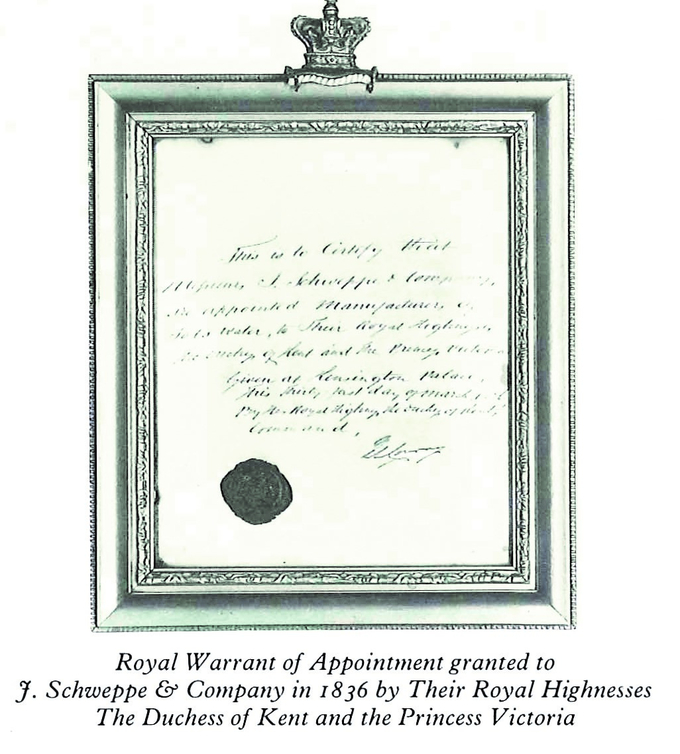

The two men were well connected and just a year after taking over the company, the quality of their product was recognised with a Royal Warrant as manufacturers of soda water to Their Royal Highnesses, the Duchess of Kent and The Princess Victoria. In August 1837, two months after ascending the throne, Queen Victoria granted a new Royal Warrant to the company. Schweppes has since been honoured with a Royal Warrant of Appointment by every successive British monarch, with the exception of King Edward VIII whose reign was so short that no Warrants were granted.

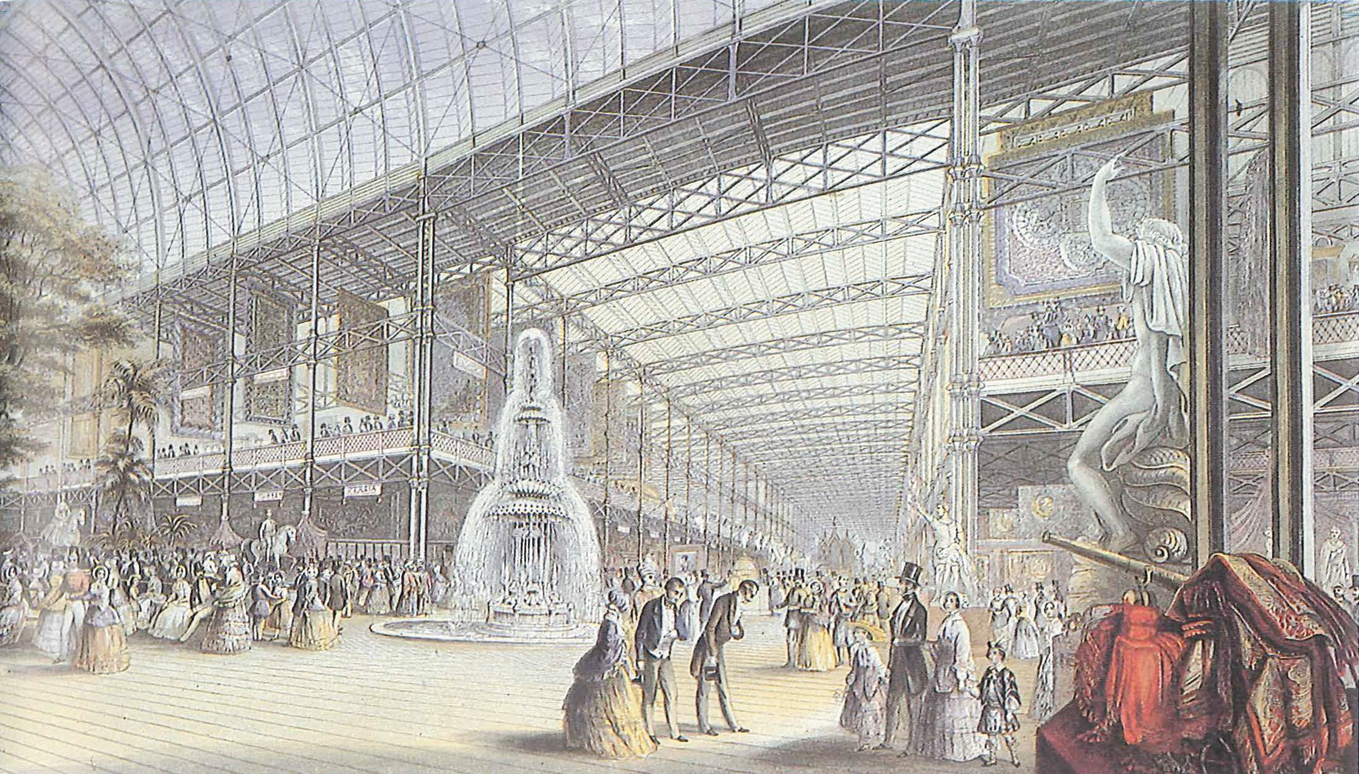

The Great Exhibition of 1851 was an event of huge importance to Great Britain and to Schweppes. The Exhibition was held in a purpose-built glass and iron structure erected in Hyde Park known as the Crystal Palace. At nearly 2,000 feet long it covered more than 18 acres and housed exhibits by manufacturers from all over the world, attracting six million visitors. Schweppes was one of those exhibitors, but more importantly was also the contracted sole supplier of refreshments at the Exhibition. Schweppes paid £5,500, then a hefty sum for the privilege and it is one of the very first examples of such sponsorship by a brand. We now take it for granted that events such as the Olympics will be sponsored, but in the Victorian era this was a new concept.

Schweppes range of mixers

The new owners were innovators and a year after acquiring the business introduced Schweppe's Aerated Lemonade (in 1835).

Lemonade had long been drunk as a thirst-quencher but as a still drink. Carbonated lemonade was a new development and the first in what would become a range of Schweppes mixers (although two invoices from 1821 show that the company supplied ginger beer from time to time).

In the 1870s Schweppes launched Tonic Water and Ginger Ale - the latter supplied either dry or sweet. Despite its remaining a peculiarly British drink for nearly a century, the importance of tonic water to the company can't have been foreseen when the new product was launched. (Tonic water did not become popular in America until after Schweppes started bottling there in 1953. And it is only in recent decades that tonic water has become popular in countries such as France and Spain.)

The first evidence of Schweppes making a cola appears in a company minute but the product did not appear on price lists until 1916. The 1920s and 30s saw the launch of Schweppes sparkling fruit juices: Orange, Grapefruit, and Lemon. Bitter Orange and Bitter Lemon followed in May 1957, made possible by advanced in fruit processing.

The modern day

The business that Jacob Schweppe established in 1783 has grown to become part of an international conglomerate with an internationally recognisable household brand name. Despite this and Jacob's Swiss roots and name, Schweppes feels a distinctly English brand and it's fitting that Schweppes Tonic Water, the world's first, remains the world No.1 brand.

Today's global carbonated soft drinks market is worth over $300 billion with some 190,000 billion litres consumed annually. Johann Jacob Schweppe started that - something remembering next time you open a bottle or can and hear that distinctive sound of pressurised gas being released - Schhh...

Join the Discussion

... comment(s) for Schhh... you know who. The story of Schweppes

You must log in to your account to make a comment.