Story

The term highball appears to have emerged during the 1890s with the first known written mention appearing in a play, My Friend From India by Ha Du Souchet in 1894 with a character called Erastus saying "Talking about drinks, I think I'll have one. (enter Jennings) Jennings, bring me a high ball of whiskey."

Then in his 1895 The Mixicologist Chris Lawlor of the Burnet House, Cincinnati includes a "High Ball" with the instruction "Put in a thin ale-glass one lump of ice; fill with syphon seltzer to within an inch of the top, then float one half jigger brandy or whiskey."

On the preceding pages Lawlor also features a "Brandy and Soda" with the instruction, "Put two or three lumps ice in this lemonade glass, one jigger brandy; pour in one bottle of club soda." This is followed by the fabulously named "Splificator", a drink that in all but name is a Whiskey Highball. According to the learned David Wondrich, 'splificated' was Irish slang for 'drunk', so perhaps the whiskey with an 'e' in Lawlor's Splificator is Irish whiskey.

1895 The Mixicologist by Chris Lawlor

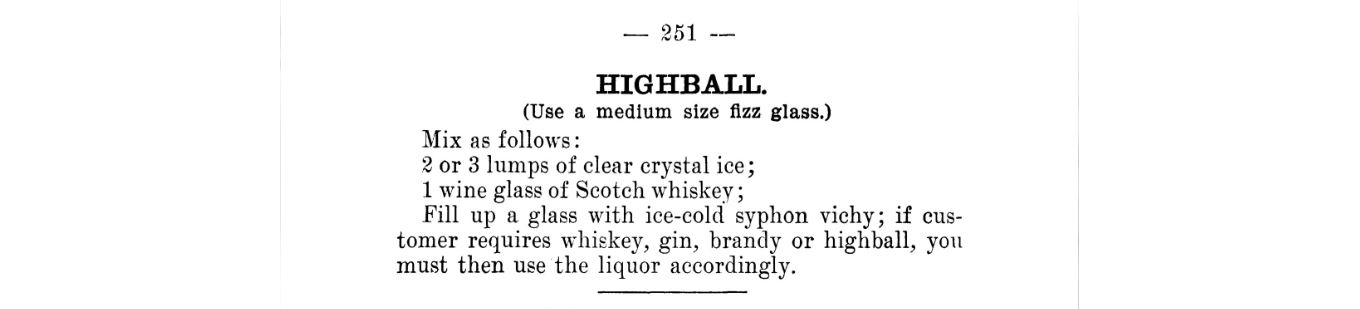

The "Highball", now spelt as one word, the appears in Harry Johnson's influential 1900 Bartenders Manual.

1900 Bartenders Manual

Patrick Gavin Duff's claim

In his 1934 The Official Mixer's Guide, Patrick Gavin Duffy comments, "It is one of my fondest hopes that the highball will again take its place as the leading American Drink. I admit to being prejudiced about this - it was I who first brought the highball to America, in 1895. Although the distinction is claimed by the Parker House in Boston, I was finally given due credit for this innovation in the New York Times of not many years ago."

That New York Times reference appears to be a letter written by Duffy on 22nd October 1927 to the Editor in response to an editorial piece in the paper. He starts, "An editorial in The Times says that the Adams House, Boston, claims to have served the first Scotch highball in this country. This claim is unfounded."

He goes on to tell of how in 1894 he opened a little café next to the old Lyceum in New York City and that in the Spring of that year, an English actor and regular patron, E. J. Ratcliffe, one day asked for a Scotch and soda. At that time Duffy did not carry Scotch but this request and the growing number of English actors frequenting his bar led Duffy to order five cases of Usher's from Park & Tilford. Duffy claims that when the shipment arrived he "sold little but Scotch highballs", consisting of 'Scotch, a lump of ice and a bottle of club soda'. His letter finishes, "Shortly afterward every actor along Broadway, and consequently every New Yorker who frequented the popular bars, was drinking Scotch highballs. In a few years other Scotch distillers introduced their brands and many were enriched by the quantity consumed in this country. Actors on tour, and members of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery of Boston, who came here annually to attend the Old Guard Ball, brought the new drink to the Adams House."

Duffy's letter to The New York Times mentions Adam House in Boston while the reference in his subsequent book talks of 'Parker House'. Both are plausible Boston locations but does this confusion mean we should not take any of Duffy's claims for being the first to make Scotch Highballs in America seriously? The Times merely published Duffy's letter to the editor, the paper did not substantiate or even 'give credit' to his claims.

Tommy Dewar's claim

Tommy Dewar of the famous scotch whisky brand also laid claim to inventing the highball in an article published in 1905 in the Eveningstatesmen were he claimed to have discovered the "highball" 14 years earlier. "It came about in this way," he said today. "I was walking along Broadway with several friends when one of them asked me to go into a saloon and have a 'ball'. As I was in that humour myself I consented. When we made our wants known to the bartender, he places before us small whiskey glasses. "'Beastly small glasses', remarked my friend. "I suggested to the bartender that he give us high glasses so that my companion could have a 'highball', and thus he satisfied. He found the right kind of glasses and we had what I have been told was the first scotch 'highball'."

The railroad connection

In his 2003 The Joy of Mixology, Gary "gaz" Regan explains that "Highball is an old railroad term for the ball indicator connected to a float inside a steam train's water tank which told the conductor that there was enough water in the tank and so the train could proceed. Apparently, when the train was set to depart, the conductor would give the highball - two short whistle blows and one long". Gary explains that this term was apt as the drinks consist of two shots of liquor and a long pour of mixer.

Real origins are English

As with so many things in the world of booze, Highballs originated in England. Indeed, sparkling drinks originated in England.

British coal-fired glass making led to the development of bottles that were strong enough to withstand the high pressure of carbonated drinks and this led to the first sparkling wine being produced in London around 1665 by adding yeast and sugar to imported French wine. (French sparkling wine production did not commence until the end of that century.)

Naturally carbonated mineral waters were valued for their medicinal value from before the time of Hippocrates who praised them, while the German town Selters started bottling and shipping its naturally carbonated spring water around the turn of the 18th century - hence the term seltzer water.

Artificially carbonated water dates back to 1767, when Englishman, Joseph Priestley successfully dissolved carbon dioxide in water.

Torbern Bergman commercialised Priestley's discovery and by the late 1700s, bottled artificial soda waters were competing with natural mineral waters. In 1792, Johann Jacob Schweppe (Schweppes) set up shop in London and in 1807 Henry Thompson received the first British patent for a method of impregnating water with carbon dioxide.

The English gentry had developed a taste for sparkling wine and brandy was also very much in fashion so it's understandable that when bottled carbonated water became available it became fashionable to mix it with brandy, a drink which by the early 19th century was very popular with wealthy London gentleman. Only the ice was missing to make this a Brandy Highball. (Ice did not become fashionable until the mid-1880s and even as recently as the 1960s, Scotch and soda were commonly drunk in the UK without ice.)

The Napoleonic wars inconveniently interrupted supplies of cognac between 1803 and 1815 so London's gentlefolk temporarily took to scotch whisky as an alternative. By the late 188o, this temporary switch became more permanent as the phylloxera plague decimated French vineyards, practically halting cognac supplies. Also, thanks to Prince Albert purchasing, Balmoral in 1852, what Queen Victoria described as "my dear paradise in the Highlands", all things Scottish became fashionable.

The popularity of Scotch & Soda was also helped by the carbonisation of water being heavily industrialised in the 1830s. This also saw the start of the American soda craze with John Matthews of New York and John Lippincott of Philadelphia both starting to manufacture soda fountains in 1832. By the 1850s flavoured bottled carbonated water started to appear with ginger ale first bottled in Ireland.

The term 'highball' may have come from the American railroads (which developed rapidly between 1828 and 1873) but may also have English and/or Irish roots with the term "ball" being a common term for a glass of whiskey in Ireland and more specifically in golf club bars in late 19th century England, a term for a whisky served in a high glass.

The whisky & soda frequently featured in British TV sitcoms during the 1960s and the soda siphon is a vital prop in many movies made prior to 1970. Thanks to the resurgence of gin, the G&T is now more fashionable than ever - perhaps it's time to both re-examine the humble Highball, and with it the Scotch & Soda.