Words by Jared Brown & Anistatia Miller

Few metropolises can boast a drinking history that spans 2,000 years. London not only holds that history, but in London’s bars you can ponder this lineage over some of the best mixed drinks in the world today.

It all started when the Romans landed in Kent in 43 AD, establishing a settlement on the River Thames which they named Londinium. Taverns were among the trove of home comforts they brought with them - along with edible snails, doves, broad beans, walnuts, cabbages, dormice, ground elder, and dovecotes. When they went home, 400 years later, the taverns remained. (Alas, so did the snails, ground elder, dormice, and cabbages.)

Where else could Geoffrey Chaucer's company gather before setting off to visit the shrine of St Thomas a Becket in his 1387 Canterbury Tales, if not in the hospitable Tabard Inn in Southwark? The Ship & Turtle in Leadenhall and The Bear on the Strand were the only other London taverns until 1552, when an Act of Parliament licensed the opening of 40 new houses.

More than a place to drink in Shakespeare's day, Bishop John Earle said it best when he commented: "A tavern is the busy man's recreation, the idle man's business, the melancholy man's sanctuary, the stranger's welcome, the inns'-of-court man's entertainment, the scholar's kindness, and the citizen's courtesy."

The coffee-house was a contender to this throne during the mid-1600s, not only serving as a caffeinated forum for lively debate, but the birthplace of Lloyd's of London (in Edward Lloyd's coffee-house) and the stock exchange (at Jonathan's Coffee House in Change Alley). Yet legend tells us that the brewed bean wasn't the only beverage served in these centres for conversation. Limmer's Hotel & Coffee-House, at the corner of Conduit and George Streets, is cited by many historians as the birthplace of the Collins.

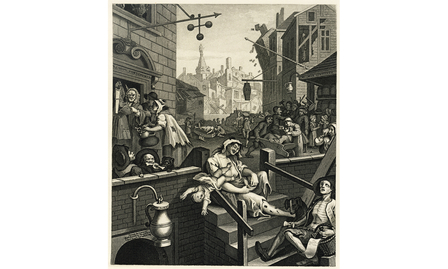

The Gin Craze of the 1700s put a strain on both the city's traditional drinking establishments, as 7,000 cheap gin shops poured millions of gallons of questionable booze for less than a penny a serving, the effect infamously depicted in Hogarth's 1751 engraving. Fortunately, by the 1790s, Parliament plugged the flow (as they did for that other scourge - coffee), but not the taste for gin, and a new drink appeared in a public house on Downing Street.

On 16 March 1798, the Morning Post & Gazetteer reported how a publican in Downing Street had erased his customers' tabs after winning a lottery. The next week, on 20 March, the same publication satirically listed the details of 17 politicians' pub debts, including this reference to the prime minister: "Mr Pitt, two petit vers of 'L'huile de Venus', Ditto, one of 'perfeit amour', Ditto, 'cock-tail' (vulgarly called ginger)."

The simple concoction of gin and ginger syrup, to which it referred, also made its way to another new venue. Not a tavern nor a pub; nor a gin shop or a coffee-house. The gin palace emerged as a garishly decorated and brightly lit sanctuary from the grey reality of London's daily life. Author Charles Dickens extolled its wonders in his 1836 collection of stories, Sketches by Boz, when he wrote: "All is light and brilliancy... the gay building with the fantastically ornamented parapet, the illuminated clock, the plate-glass windows surrounded by stucco rosettes, and its profusion of gas-lights in richly-gilt burners, is perfectly dazzling when contrasted with the darkness and dirt we have just left.

"The interior is even gayer than the exterior... Beyond the bar is a lofty and spacious saloon...with a gallery running round it, equally well furnished. On the counter, in addition to the usual spirit apparatus, are two or three little baskets of cakes and biscuits... Behind it, are two showily-dressed damsels with large necklaces, dispensing the spirits and 'compounds'."

Compounds was a colourful term for mixed drinks. Far more sophisticated than the sling, the cocktail (a sling with dashes of syrup or bitters), punch, cups, and Collinses appealed to Victorian Londoners' love of anything new and different. And then a champion of trend raised the bar even further a few years later.

At the height of his career, London 's first celebrity chef Alexis Benoit Soyer earned more than £1,000 per year (£100,000 in today's market) commanding the Reform Club's kitchen. Besides creating the sumptuous Reform Raclettes of Lamb that are still served in this exclusive Pall Mall club, he created the world's first blue drinks and jelly shots.

The popularity of Schweppes soda water products inspired Soyer to create, in 1850, his own signature soda: Soyer's Nectar. Composed of raspberry, apple, quince and lemon juices, spiced with cinnamon and tinted bright lake blue (presumably with dried gentian petals), Soyer's Nectar was initially touted as a hip hangover cure. When mixed with sherry, The Sun declared it far tastier than a Sherry Cobbler. The Globe recommended adding a tot of rum instead.

The next year, Soyer's runaway best-seller The Modern Housewife or Ménagère offered up recipes for Gold Jelly, made with eau-de-vie de Danzig; a Maraschino Jelly; and Rum-Punch Jelly. Blue drinks. Jelly Shots. But Soyer was not finished challenging Londoner's drink expectations.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 and its fabulous Crystal Palace opened to great fanfare in Hyde Park. Along the park's southern border, where the Royal Albert Hall now stands, Soyer opened Soyer's Universal Symposium of All Nations. Within this complex of lavishly-appointed dining rooms he opened The Washington Refreshment Room - an American bar that offered 40 different concoctions including his own Soyer au Champagne plus "flashes of lightning, tongue twisters, oesophagus burners, knockemdowns, squeezemtights...brandy pawnees, shandygaffs, mint juleps, hailstorms, Soyer's nectar cobblers, brandy smash, and hox genus omne".

Although he had interviewed "an eccentric American genius, who declared himself perfectly capable of compounding four [cocktails] at a time, swallowing a flash of lightning, smoking a cigar, singing 'Yankee Doodle', washing up the glasses, and performing the overture to the Huguenots on the banjo simultaneously", he selected a West Londoner named William York to preside over the bar.

Soyer's extravagant creation only lasted six months before poor financial management closed its doors. However, producing cutting edge food and drink for the wealthy was not his primary concern. This creative genius turned his attentions away from the posh and the outrageous to the humanitarian. He designed the portable soup kitchen that fed 26,000 victims of the potato famine in Dublin on a daily basis. And he constructed the camp stove that saved the lives of tens of thousands of British troops fighting in the Crimean War, before he passed away in 1858.

His potations were not lost or forgotten. A year after Soyer's death, Jerry "The Professor" Thomas braved "the dangers of a transatlantic voyage" and found himself a guest slot as "a genuine Yankee professor" mixing drinks in London's Cremorne Pleasure Gardens. Among the amusement park's many delightful entertainments during the summer of 1859 were an American-style bowling green and an American bar - The Bowling Saloon - which lasted for two seasons.

Thomas was evidently inspired by London's drink culture. He added two of Soyer's recipes - Punch Jelly and Soyer's Gin Punch - as well as a winter-time favourite, the Tom & Jerry (inspired by Pierce Egan's characters and already popular when Mr. Thomas was three years old).

The speed at which the shipping vessels could make the Atlantic crossing under steam power brought about another American import that changed the London drinks menu: phylloxera. Arriving on American vine stock, a plague of phylloxera aphids eradicated cognac, claret, and sherry from drinks menus for nearly 30 years. More than one author came to the aid of Victorian hosts. Forward-thinking Mrs Beeton included a Gin Sling and a Mint Julep in her 1861 Book of Household Management.

But not all British palates adapted readily to the sweetness of American drinks, nor their tooth-numbing coldness. Henry Porter and George Roberts published their distaste for this "colonial" invasion, in 1863, remarking that: "For the 'sensation-drinks' which have lately traveled across the Atlantic we have no friendly feeling... we will pass the American bar... and express our gratification at the slight success which 'Pick-me-up,' 'Corpse-reviver,' 'Chain-lightning,' and the like, have had in this country." Porter and Roberts published their homage to British drinks, Cups and Their Customs, six years later.

William Terrington surveyed the cornucopia of British tipples that same year in his Cooling Cups and Dainty Drinks. From wines, spirits, cordials, liqueurs and syrups, bitter drinks, cups, cocktails, and punches, it was obvious that London's drink repertoire had evolved.

Piccadilly Circus became the epicentre of London's cocktail universe. The Café Royal opened in 1865 at 68 Regent Street. Felix William Spiers' and Christopher Pond's The Criterion Restaurant & Theatre opened in 1874 at 224 Piccadilly. Its Long Bar has its place in history as the location where Dr John H Watson ran into an old acquaintance who introduced him to Sherlock Holmes in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's 1887 A Study in Scarlet.

French chef George Auguste Escoffier partnered with hotelier César Ritz, in 1890, to open Richard D'Oyly Carte's Savoy Hotel on the Strand. The elegant lodgings were enhanced with even more amenities a mere eight years after it opened, including an American Bar.

D'Oyly Carte purchased Claridge's Hotel, in 1894, which he also refurbished and reopened four years later with an American bar and a female head bartender named Ada Coleman. (The year before his death, in 1901, D'Oly Carte purchased another hotel that sported a popular bar, The Berkeley.)

With the death of Queen Victoria and the enthronement of her son, Edward VII, London society spread its cosmopolitan plumage like a grand peacock. Cocktails flowed at elite hotels, cafés, and gentlemen's clubs even when the First World War draped a dark veil over the nation's spirits.

Prohibition in the United States tipped beverage scales toward London. Harry Craddock sailed from New York's Knickerbocker into Savoy Hotel immortality. Returning from the war, Scot barman Harry MacElhone illuminated the life of the affluent Bright Young People at Ciro's Club on Orange Street before taking over the famed New York Bar in Paris in 1923.

A drinking triangle formed around Piccadilly Circus. On any given day a reveler could have a lunchtime meet up with old school chums at the Carlton Club on Pall Mall or the Landsdowne Club on Charles Street. Head over to the city's finest hotel bars - Savoy, Claridge's, Berkeley, Dorchester, Grosvenor House, Park Lane, the Ritz, Hyde Park, Piccadilly, or Mayfair - for an afternoon sip. Savour a pre-prandial Martini at Quaglino's on Bury Street, Coq D'Or on Stratton Street, Prunier's on St James's, or the San Marco on Mayfair Place. And then trip the life fantastic at the Café Royal, Café de Paris, and the London Casino.

After a brief hiatus during the Second World War, Londoners returned in full force to their favourite watering holes with gentlemen such as Ian Fleming, Noël Coward, and Kingsley Amis leading the charge.

The revelry ramped up to an even high pitch during the Swinging Sixties. The younger generation rarely ever adopts its parents' drinks and Sixties clubbers were no exception. Hotel bars and gentlemen's clubs were too quiet, too reserved. The Playboy Club in Hyde Park was a hot ticket. Rock 'n' roll was king and clubbers were drawn to the music like paisley- and stripe-clad moths to a 100-decibel flame. They mimed the orders of rock's elite: rum and coke, whiskey and coke, gin and tonic, vodka and orange, straight tumblers of spirits. What's good for John, Paul, Mick, Keith, Freddie, and Moonie is the order, right? Right.

Then the bubble burst. The worst economic recession since the 1930s, strikes, riots, and a general feeling of angst and anger punched 1970s London right in the olives. The cure? Disco. Piña coladas, scorpions, and Blue Hawaiians offered style on the cheap. Though amid the leather chairs of St James's clubs and Mayfair's hotel bars, a well-executed cocktail could still be procured from Peter Dorelli at the Savoy, Gilberto Preti at Dukes, and Salvatore Calabrese at the Lanesborough.

Before the decade ended, a pivotal character went behind the bar at the Naval & Military Club on St James's Square. He devoured page after page of old cocktail books. He tested each recipe, learning and perfecting the best ones. Call it destiny. Call it sheer luck. Dick Bradsell trained as a bartender during the city's bleakest drinking period.

During the next two decades, he mastered the classics, trained aspiring young talents, campaigned for quality spirits, fresh juices, and garnishes. And he created a retinue of modern classics: the Pharmaceutical Stimulant (aka: Espresso Martini), the Bramble, the Russian Spring Punch. London's spirit rose from the ashes like a phoenix as The Atlantic Bar & Grill - featuring Dick's Bar as a centrepiece - and The Player titillated 90s hearts and palates.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Today, outstanding drinks executed by great young and old talent can be found around the globe. Yet each and every one of them keeps a close eye on London. Why? Because what's next in most places is what's here now.

Join the Discussion

... comment(s) for London and its cocktails

You must log in to your account to make a comment.