Are you a Discerning Drinker?

Join thousands of like-minded professionals and cocktail enthusiasts, receive our weekly newsletters and see pages produced by our community for fellow Discerning Drinkers.

Words by Philip Duff

“What, actually make it? Like, for real?” I looked quizzically at Jean-Sébastien Robicquet, and slurped on my Negroni.

In the six years I've known him, he's bounced a great many ideas off me, almost all of them over a Negroni or two. Some of them - like La Quintinye Vermouth Royal - came to fruition; some did not. His company, EWG Spirits & Wine, has been growing exponentially, and I've been pretty busy myself. Anything that didn't seem do-able from the get-go probably wasn't going to become more do-able, so we'd drop it. But then, we'd discussed this particular topic before...

In 2009, I met Audrey Fort (at Tales of the Cocktail, since you ask); presently the EWG portfolio manager in the US, she was then the marketing & business development manager. EWG signed on as clients for my little on-trade consulting firm, Liquid Solutions, and off we went. One of the first things I did was to hit the books; was there a history of gin based on grapes, like EWG's flagship brand G'Vine? It turned out there was, and not just the well-known Menorcan gin Xoriguer, which traces its history to the late 1700s. No, what I unearthed went back further - way, way back further.

I was living in the Netherlands at the time, and had been for 14 years, so I was able to read Dutch. I found a book called Genever in the Low Countries ("Jenever in de Lage Landen"), only ever published in Dutch in 1996, and out of print. It is a magnificent book, a worthy addition to the library of any serious spirits lover, immaculately researched and footnoted by its author, professor Eric van Schoonenberghe. Professor van Schoonenberghe is very much in the Indiana Jones school of professoring; as well as being one of Europe's leading experts on distilling and brewing, he personally trained up three generations of distillers at the family-owned Filliers distillery in Baarle-Nassau (Belgium), and founded both the Genever Museum in Hasselt (Belgium) and the Genever Museum in Schiedam (Holland).

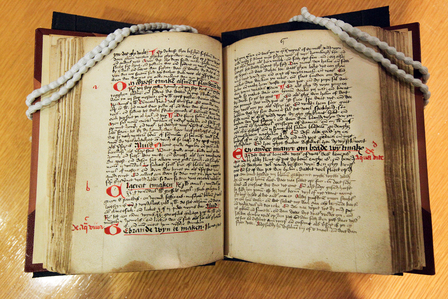

In this book, van Schoonenberghe writes about a recipe he found in the Sloane Manuscripts, part of the 100,000-item bequest of scientific articles and items left to the British nation by Sir Hans Sloane on his death in 1753. Sloane's collection was so large it necessitated the building of the British Museum, which in due course split off the books into the British Library.

This recipe was called "Om Gebrande Wyn te Maken": "making burned wine". In his book, van Schoonenberghe explained the recipe was thought - by dialect analysis - to have been written in the region of Arnhem/Apeldoorn in the Netherlands, dated from 1495, and specified ingredients for a botanical spirit distilled from wine. This spirit had an incredible array of botanicals, all the more if you consider that, in 1495 - more than a century before the Dutch or English East India companies were founded - all these exotic spices would have had to be hand-carried to the Netherlands on the Silk Road from China and Asia. Nonetheless, the recipe contained nutmeg, cinnamon, galanga, seeds of paradise, cloves, ginger, sage, cardamom and juniper, variously macerated or distilled on a base of wine, almost certainly from the La Rochelle/Charente region, where Cognac is situated.

So far, so good, but nothing so very exciting; history abounds with such recipes, and indeed Jacob van Maerlant te Damme's 1269 "Der Naturen Bloeme" encyclopedia details recipes for cooking juniper berries in wine - but purely in the context of it being a medicine. Johannes van Aaltier had a similar enough recipe in 1351, but that was emphatically medicinal; he wrote it during a plague epidemic.

No-one knows when medicine became recreation, but it's fair to say that the practise would have been started by the wealthy - and the decadent. The sort of people whose recipe for a 10-liter batch started with 12 nutmegs, which were then worth more by weight than gold, and included just about everything expensive and obscure, botanicals-wise, that East India and Asia had to offer. The sage and juniper were the cheapest, most local ingredients in what we had by now begun to call Gin 1495. We know this was a recreational recipe because it was in amongst the kitchen, food recipes; there are plenty of medicinal recipes in the book - it's spine title in the Sloane Manuscripts is Medicinal Tracts - but our gin recipe isn't there. Another very big deal.

Just a year prior, in 1494, a certain Friar John Cor in Scotland was recorded as being granted a large amount of malt to make aqua vitae for the king, a record seen as the first written proof of recreational whiskey making. Three years later in 1497, spirits were being taxed by the Amsterdam authorities, and by the time Casper Jansz. Coolhaes published A Guide To Distilling in the Netherlands in 1582, the standard base for distilled spirits had become grain, not grapes; Coolhaes wrote that grain spirits were not only being called brandy wine, but were being "paid for and drunk as if they were brandy wine".

The team at G'Vine were delighted that we'd unearthed not just historical proof of grape-based gin, but also a very important new contribution to the history of juniper spirits. Generously, they let me publish that information, and it has become part of the canon of serious gin history. Just like, I'm pleased to say, the debunking of the Doctor Sylvius myth, about a Leiden University professor (or professors, depending on who you ask) who invented genever. Van Schoonenberghe dismantles this myth effortlessly. So I toured around the world, giving gin trainings, mentioning 1269 (van Maerlant), 1495, and how Sylvius (who did exist, but never did a damn thing with genever, which was already being taxed when he was a mere minus 117 years old) was not the man. Good times!

Then came the fateful chat. The idea had been batted around before; put it in the G'Vine bottle and sell it as a special edition? Gift it to an elite cadre of gin-lovers around the world? Make it in PET-bottles and send it to ambassadors and sales reps to use in their trainings?

This time was different though; I spotted a gleam in Jean-Sébastien's eye that I've seen before. Gin 1495 was happening.

First off, we recruited Dave Wondrich. As well as possessing an impressive beard and a house full of books, Dave knows as much as any man alive about old distilled-spirits recipes, and he's got quite the track record in rejuvenating them. We decided Dave and I would spar over an exact replica of the 1495 recipe, soon to be titled "Verbatim". It was thought that we should also put our own spin on things, so we decided to make a second version as well; building on a base of Verbatim, a panel comprising myself, Dave Broom, gaz Regan, Gary Sharpen (Cocktail Lovers) and Holly Motion (Drinks International) added in hints of angelica, more sage, more juniper and a faint note of citrus peel to create what was termed "Interpretatio".

The process was, if anything, even cooler than the research. Myself and Dave wrestled over the recipe. It was clear enough, but, in an era where trade secrets were the only way to stay in someone's employ and not, y'know, starve to death, what would the distiller have omitted from the recipe? We tried to imagine who this distiller, 519 years ago, was; man or woman? (Very possibly a woman: brewing and distilling was part of the kitchen staff's duties in the great houses of the day). Who was the head of the household? (Given the rare botanicals, we gambled on it being a rich, well-connected merchant, but it could easily have been an aristocrat; Holland had enough of them back then). How often was this made? Probably every month or two, depending on how many guests the head of the household wanted to receive - and impress. What would it have tasted like to someone in 1495?

This was a time when every single botanical except sage and juniper was entirely alien to the European palate, and the only sweetener anyone would have was - perhaps - some honey. There was sugar in Europe in the 1400s, but it was expensive as cloves or nutmeg - i.e., as expensive per gram as gold - and if they'd added it to the 1495 recipe, it's certain the master would have insisted it be mentioned in the recipe, which drips with his wealth and ostentation. We could assume that some of the heads and most of the tails were cut; that was a distiller's secret dating back millennia.

After an unhurried lunch at Villevert, EWG's headquarters, Dave Wondrich came up with a solution to one of our problems, which goes to show that beer and steak tartare is a much-overlooked aspect of creativity. The recipe starts with "wine and/or the mother of wine", which can refer to lees (dead residual yeast and other bits and bobs leftovers when you distill wine) or pomace, the skin and stalks left over after you press grapes during winemaking. Dave, ever a man for the flavour he lovingly terms "funk", suggested blending in some marc (pomace distillate). Under the watchful eye of Jean-Sébastien, we did just that, and it transformed our recipe. Verbatim was done! It was Friday in Cognac. Time for wine. But first, a celebratory Negroni...

At the weekend, Dave flew back to Brooklyn and I toodled over to London to meet up with the second panel, plus Jean-Sébastien and the senior management of EWG. The agency had arranged something remarkable, at least, so it seemed to me: we were going to the British Library to view the manuscript itself. As our guide that morning explained, the British Library is a working library, not a museum of the book - so we could see it. This was going to be very cool.

When I entered the room, my immediate thought was "Oh good. They've given us a copy - no need to worry about spilling coffee on it". (This thought won't surprise anyone who's ever had dinner with me) Even from across the room, I could see that this small leather-bound volume had clean, bright white pages and vibrant, rich coloured text - did I mention it was all handwritten? The group milled around it, and I pointed out the key points: a margin scribble "de aqua vina" just to the left of the title "Om Gebrande Wyn Te Maken", and the crucial word "gorsbeyn", that van Schoonenberghe had identified as "juniper", and which confirmed we were looking at the only known copy of the oldest recipe for recreational gin in the world, a gin that pre-dates the word "gin'.

Close-up of the Making Burned Wine manuscript with, about 10 lines down from the top, in the dead center of the image, the words 'gorsbeyn of dameren'.

At the end, I was allowed to read through the recipe, and - stupid, right? - I was amazed that it was exactly as it had been described in "Genever In The Low Countries". The compulsion to display wealth possessed by the person who commissioned this book hadn't stopped at the gin; the recipes had been written out by a scribe on what the British Library curator described as the most expensive paper available at the time, which is why it still looked fresh and new, and why the gall-ink was still rich and colorful, hardly faded. It was beautiful. It is beautiful. Go and see it.

After a brief pitstop at the Genever Museum in Schiedam, the Netherlands, to place Gin 1495 in context, it was onwards to Cognac for round two: Interpretatio.

This proved, even with prodigious amounts of steak tartare, snails, beer, Negronis and Bordeaux, to be a tricky affair. We had some memorable early experiments with high-sage-content, with high-citrus, and some others I'd rather not mention. Towards the end of the week, Jean-Sébastien, who has a very fine palate, began to exchange concerned glances with Didier, who was running the stills. In the end, we plumped for mild concentrations of citrus peel, iris (which gave wonderful, vaguely agricultural aromas), sage and juniper. Once again, we tried to place ourselves in the shoes of this distiller from five centuries ago. In a room full of creative, urban drinks professionals, used to pushing the envelope, it took us the longest time to realise that less was more; that our distiller would have been happy to make a few such small adjustments to the excellent initial recipe as we had made. Interpretatio was a fact.

In all of this, Jean-Sébastien was a constant: never interfering, but always ready to give an unvarnished perspective on the latest distillate. As owner of EWG, he's famed as being the producer of Ciroc vodka for Diageo. He's a top-class distiller and oenologist by profession, and personally created not only G'Vine gin, but also June liqueur, La Quintinye Vermouth Royal, and (together with Carlos Camarena) Excellia tequila. His greatest contribution was yet to come, though: in discussions with him and the agencies, it was decided that Gin 1495 would be his gift to the world of gin. A maximum of 100 editions, in a huge Hogwarts-style leather-bound book that hinges open on a secret button to reveal sample of Interpretatio and Verbatim, plus a facsimile of the text. Only to be auctioned for charity (the first two for the benefit of the Benevolent, house charity of the Gin Guild - get your bids in before December 01 here.

The finished Gin 1495 package

Additional copies of Gin 1495 will be donated to the Genever Musea in Holland and Belgium, the Ginstitute (London), the Museum of the American Cocktail (New Orleans) and the visitor experiences of other major gin brands, if they would like. And as if that's not enough, EWG are also paying for the original "Om Gebrande Wyn Te Maken" text to be digitised and placed in the British Library's online archive, available for the whole world to see, before the end of this year.

It's my wish that this stimulates some more research into the origins of this category that we all love and - who knows? - maybe there's an even older recipe out there.

Join the Discussion

... comment(s) for Discovery & remake of the World's 1st known gin

You must log in to your account to make a comment.