How Sherry is made

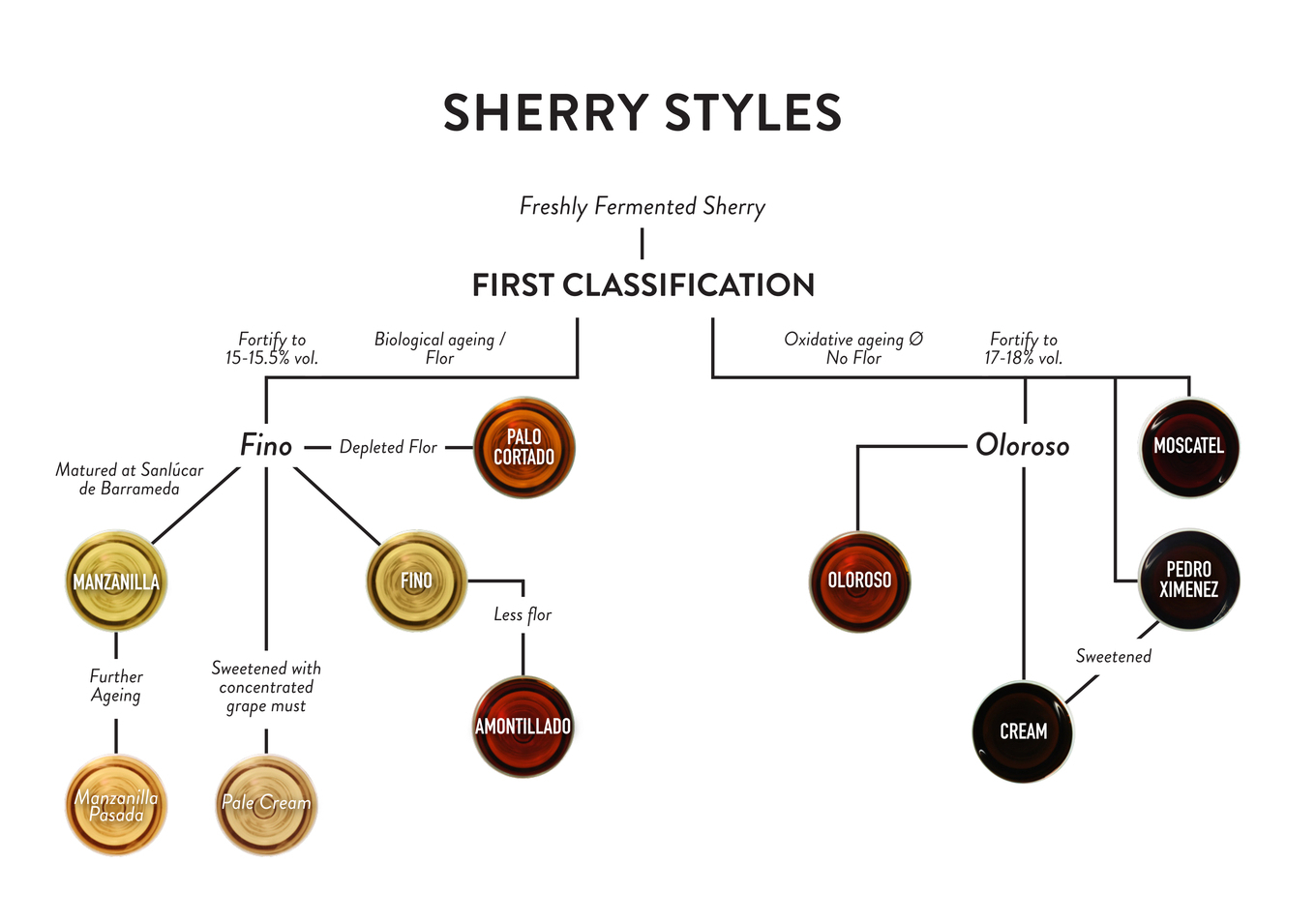

There are numerous styles of sherry, from bone-dry Fino and Manzanilla sherries to sweet Muscatel and Pedro Ximénez sherries. All these sherries are made from four base sherry wines, as depicted in the diagram above.

Muscatel and Pedro Ximénez sherries are each named after the white grape variety from which they are made. Due to late harvesting and sun-drying, these two styles of sherry wine are sweet, and are bottled as 100% single-varietal sherries, and also blended with the two other sherry base wines: Fino and Oloroso to produce other styles of sherry.

Fino and Oloroso sherries are made from a white grape variety called Palomino, which is fermented into a dry base wine and then fortified with grape spirit. After fermentation, Palomino wines are classified to either encourage a natural layer of yeast called flor to develop on the surface of the wine in the cask, or to be fortified to a higher alcohol strength that prevents flor yeast from developing.

Those wines with flor yeast are protected from oxidation, so they age "biologically", developing fresh, nutty flavours, and these are called Fino (or Manzanilla if made in the coastal town of Sanlúcar de Barrameda). Wines without a flor yeast are Oloroso, and these age "oxidatively" as they are exposed to controlled oxidation in the cask.

Sherries are aged using the solera system, a method of fractional blending in which younger wines are gradually refreshed with older wines, producing complex, consistent wines that range from bone-dry to richly sweet, depending on the grape variety and presence of flor yeast. Blending after solera ageing creates additional sherry styles.

Sherry making in detail

Harvest

The start of harvest is not set by a specific date; it occurs when the grapes are ripe enough, with their sugar content reaching a minimum of 10.5° Baumé (potential alcohol), although the grapes typically reach between 11° and 14.5° Baumé.

Harvest begins at the very end of August or the first week of September, and although machines are used, much of the picking is still done by hand. The use of machines, the effects of global warming, and improved viticulture practices have led to night harvesting becoming more common to take advantage of lower nighttime temperatures.

Pressing grapes

Palomino grapes are harvested relatively early to retain freshness, then lightly crushed and pressed. Historically, pressing was in lagares by foot, but today pneumatic presses are used.

The grapes are pressed very gently to extract their juice, known as must. The aim is to extract clean, low-phenolic juice rather than colour, tannin or bitterness. This process is repeated four times, starting with light pressing and increasing pressure with each pressing to extract precious juices. As more pressure is applied with each pressing, the quality of the extracted juice declines. Only the first two pressings produce must of sufficient quality to be used to make sherry.

1st pressing - Primera Yema or Mosto Yema

The first free-run juice "Primera Yema" (literally 'first yolk') or "Mosto Yema" ('yolk must') evokes the idea of the "heart" or pure essence of the grape, and this must is used to make the finest, most delicate base wines: Fino-style sherries (Fino, Manzanilla and Amontillado). It is no coincidence that the Spanish term for fine and delicate is fino. This first light pressing produces 65% of the juice extracted from the grapes.

2nd pressing – Segundo Pie

The second, firmer "Segundo Pie" (which translates as 'second foot') pressing (less than 25% of juice) produces darker, coarser must with higher phenolic content, suited to making Oloroso-style wines.

3rd pressing – Prensas

The grape must extracted from third "Prensas" (translates as 'presses') pressing is mostly fermented and distilled to produce grape spirit.

4th pressing – Prensas

The must resulting from the 4th pressing is used to make vinegar, and the vinegar from Jerez is held in high regard.

Denomination of Origin regulations stipulate that a maximum yield of 70 litres (18.5

gallons) of must from each 100kg (220lb) of grapes pressed can be used to make sherry.

Fermentation

After pressing, the grape must is clarified through a settling process known as desfangado, which allows solids, such as grape skins, pulp, and dust, to sink to the bottom of the tank. Traditionally, this happened naturally in cool conditions, but today it is often temperature-controlled to ensure a clean, bright must. The degree of clarification is important, as too many solids can lead to coarse flavours, while too few can weaken fermentation and later impact flor development.

The clarified must is transferred into stainless steel tanks, which are almost filled, leaving room for the addition of grape must already in full fermentation, called pie de cuba. Accounting for between 2% and 10% of the total volume, the yeast in the pie de cuba helps start fermentation and ensures fermentation with a specific yeast strain that produces wine with the desired oenological and sensory characteristics.

The first phase of fermentation (tumultuous) in large stainless steel fermentation tanks at a temperature between 22-26˚C. After a few weeks, as fermentation reduces the sugars in the must, a second phase of slow fermentation starts and continues.

If palomino grape must (the vast majority of sherry wines), then the fermentation is allowed to continue until all the remaining sugar is converted to alcohol. This is unique in the world of fortified wines, where fermentation is usually stopped by adding grape spirit to raise the alcohol level above the yeast's tolerance, leaving residual sugars in the wine.

The dry, neutral white wine produced, called mosto, is 11–12.5% alc./vol. and ideally suited to fortification and long ageing under flor or oxidative conditions.

Initial classification prior to fortification

Once fermentation is complete, the cellar master must sample the 'mosta' (the correct term for the young wines prior to the fortification process) to determine whether the wine in a cask (or vat) will become a fino or an oloroso.

Pale and light wines are classified for ageing as finos and manzanillas, and their casks marked with a " ∕ " chalk mark. Heavier, darker wines are classified for aging as olorosos with their casks marked " Ø ".

In order to become a fino, a naturally occurring fungus-like growth known as 'flor' must develop on the surface of the wine while it ages in the cask. If flor yeast grows to cover the surface, the wine will develop into a fino (or Manzanilla if in Sanlúcar de Barrameda) because the floating layer acts as an air seal, preventing oxidation. This leads to an increase in acetaldehyde levels, a major contributor to the flavour of fino sherries.

To the contrary, oxidation is necessary to produce Oloroso, so wines where the flor fails, or is prevented from developing, will become olorosos.

Fortification

"Encabezado" (fortification) is the addition of alcohol to raise the strength of the wine, and after classification, the wines are fortified with the addition of 'mitad y mitad', a 50-50 blend of 95.5% alcohol by volume grape brandy and sherry wine at 12%.

Finos (and manzanillas) are fortified to 15.5% alc./vol., the ideal strength for the formation of flor, while olorosos are fortified to 18% alc./vol. to prevent the growth of flor yeasts. Crucially, flor cannot survive above 17% alc./vol. The yeast also requires a humid environment and is sensitive to heat (the ideal temperature is 22˚C).

It is worth noting that you can turn a fino into an oloroso by killing the yeast by adding more mitad y mitad to increase the strength, and/or increasing the temperature. Therefore, producers usually strive to make light mosta that is favourable to the development of flor, so they are careful when pressing grapes not to apply too much pressure as this is another key factor affecting the formation of flor.

Sobretablas

"Sobretablas" (meaning 'on the boards') is a key in-between stage in sherry-making, after fermentation but prior to the final style of sherry the wine will become, and its transfer to a solera of that style.

As the name suggests, traditionally, casks are rested on wooden planks during this observation and classification stage, but nowadays most bodegas use small stainless-steel tanks.

The capataz (cellar foreman and tasting authority in a sherry bodega) repeatedly tastes the wines over months and sometimes up to a year, assessing body and structure, aromatic delicacy versus weight, acidity and finesse, with each cask marked with a "palmas" (chalk mark) according to whether the wine is destined for:

Fino (or Manzanilla) (biological ageing)

Oloroso (oxidative ageing)

Palo Cortado or to be set aside for single cask, añada, or other rarer bottling.

Sobretablas allows time for a wine reveal its nuances and potential, rather than forcing a style upon it.

Pedro Ximénez and Moscatel vinification

Pedro Ximénez (PX) wine is made only from overripe Pedro Ximénez grapes, harvested late August / early September when fully ripe with a high sugar concentration at least 16° Baumé.

The harvested grape bunches are spread across esparto grass mats for sun-drying ("asoleo") and are covered at night to mitigate damage by morning dew and cold winds. Depending on weather conditions, this sun-drying period can last 7–15 days, during which time water evaporates, concentrating sugar, acids and glycerol content (to 450-500 grams of sugar per litre of must).

Pressing the now raisined grapes requires vertical presses, as little liquid remains inside the grapes. Once the thick must is extracted, it starts fermentation, and unlike Palomino must, fermentation is stopped by fortification with grape neutral alcohol. The fortified wine is stabilised during the autumn and winter months prior to ageing in American oak casks.

Moscatel sherry is made exclusively from moscatel de Alejandría grapes harvested at peak ripeness. As with PX, many wineries sun-dry (asoleo) Moscatel grapes to obtain wine known as "moscatel pasa" (moscatel raisin). Other wineries only late harvest, foregoing the asoleo process. Mostetel can be a combo of late harvest and sun drying. Vinification is the same as for Pedro Ximénez.

Pedro Ximénez and Moscatel are both fortified to 15 - 17% alc./vol. and aged oxidatively, often in solera.

Cask types and sizes

Historically, wooden casks of various sizes, from 16.6 litres (4.4 gal) to 900 litres (237 gal), have been used for sherry maturation, each with its own name: toneles, toneletes, bocoyes, botas gordas, botas largas, botas cortas, medias botas, cuarterones, barriles, arroba. Different types of wood have also been used historically, particularly chestnut. However, today 600-litre American oak (Quercus alba) casks, known as bota bodeguera, dominate with the occasional use of European oak (Quercus robur / petraea) for oxidative styles of sherry, particularly PX. (These are casks or butts, not "barrels"! An American Standard Barrel (ASB) used for ageing bourbon is a mere 200 litres.)

American oak is the most commonly used wood for ageing sherry because it allows steady oxygen transfer, encourages healthy flor development and, once seasoned, contributes minimal oak flavour. As well as its functionality, there is a long tradition dating back to the beginning of trade with America. Wood was shipped to Spain to make barrels and casks filled with sherry shipped back to America.

New casks are only introduced to sherry solera as a last resort, when an old, leaky cask is beyond repair. New casks must be seasoned with must or young wine, and the wine is then discarded or distilled into industrial alcohol. The cask is then seasoned with sherry-style wine for 6–24 months to remove raw oak flavours and create a stable microbial environment. This seasoning wine is also discarded as it is not suitable for sherry.

These sherry wine seasoned casks are widely exported to the whisky industry, but strictly speaking, they are not "sherry casks" as no sherry has been aged in them. These seasoned casks are ready to be used in a solera system to become sherry casks.

Casks are painted black so leaks can be spotted, and they typically remain in use for over a century before needing to be replaced.

Ageing cellars

The ageing cellars in the Sherry region are all above ground, so they are actually warehouses rather than "cellars". However, calling these architecturally splendid, often cathedral-like buildings "warehouses" doesn't do them justice. Despite their architectural elegance, these buildings are foremost designed to be functional.

Most of these buildings were constructed during the 18th and 19th centuries, with their design ensuring cool temperatures and as much humidity and air flow as possible. Their orientation minimises the impact of the sun on the roofs and harnesses the poniente's westerly currents or winds from the south, essential for the development of the flor yeast. Conversely, they block the dry, warm winds from the northeast and east.

The walls are never less than 60cm (24") thick to insulate from the high outside temperatures, and they have 15 metre high, cathedral-style ceilings with small windows on the upper parts. Doors are opened and closed to encourage drafts, and the floors are albero, a fine sandy earth that can be watered during hot, dry periods. Hoses and tap water are used to literally flood the building to regulate temperature and humidity.

Ageing

Sherry is matured whilst also being fractionally blended in a layered system of casks called a Soleraje, better known as a "Solera system". The complete system comprises several layers of butts (casks), with each layer or tier called an Andana.

It is the ground or base layer of these rows of butts, which is actually the Solera, with the subsequent rows stacked on top of this called criaderas (pronounced "cree-ad-air-ras) or escalas. The first layer, directly on top of the solera layer, is known as the '1st criadera', the next layer the 2nd criadera' and so on. There must be a minimum of three layers for the finished wine to be termed sherry, but it is common to have 10 layers, and there can be as many as 20. (Lustau have a maximum of four layers.)

Wine is drawn for bottling from the butts in the Solera layer at the base of the stack with only part of each butt's contents, never more than one-third, removed. This extracted wine is termed Saca) and is replaced with Rocíos (pronounced "roth-e-o") wine extracted from the 1st criadera layer above. In turn this is replaced with wine drawn from the 2nd criadera layer above, and so on

Although the wine must gradually move down the layers, it is not necessary for all the 'criadera' to be stacked one on top of the other, or even in the same building. These days, the wines are moved by pump and their progress tracked by a computer. Wine drawn from each butt in a layer is pumped to a holding tank to integrate wine from all the butts in that layer, then the contents of the tank is pumped to replace wine drawn from each butt in the row below. The top layer of butts in the Solera are replenished with recently fortified young wine.

The platform mounted mobile pumping machine at Lustau

The drawing off of sherry (saca) from the base (solera) layer and the replenishing (rocío) of wines removed from each successive layer (criadera) above is known as Correr escalas (running the scales).

The solera method of maturation ensures that each year the sherry of a particular brand tastes exactly the same as that sherry did in every previous year. It is common for the solera row to be a blend of thirty different vintages.

No more than one-third can be drawn out of any one butt at a time, and if that much is withdrawn, then the procedure cannot be repeated more than three times in any one year. Usually, only 20% is drawn as saca.

Each style of sherry has its own solera, through which that wine moves during maturation, being blended with previous years' wines as it goes.

Minimum age & Vintage sherries

The average age or "vejez media" in the solera is calculated from the total volume of wine in the system, the number of levels in the system, and the volume of wine removed as saca in a year. The older the wines, the more difficult it is to accurately assess its average age.

2 years average age = minimal legal age for bottling

4 years average age = typical average age sherries are bottled at

12 years average age = certified average age statement

15 years average age = certified average age statement

2o years average age = V.O.S. (remember "Very Old Sherry")

30 years average age = V.O.R.S. (remember "Very Old Reserve Sherry")

Recent changes to the regulations allow for vintage or 'Añada' sherries. However, it is more common for labels to proudly declare the date when the solera from which a sherry is produced was originally established. During the time in the solera, the wine loses 3-4% water each year through evaporation, so concentrating flavours. 20-year-old sherries typically lose 45% of their volume during ageing.

It's worth noting that the darker colour of older sherries is due to the effect of oxidation rather than from the oak casks, as the casks used are so old that they no longer impart colour to their contents.

Fino & Manzanilla versus Oloroso in a Solera

Fino and Manzanilla sherries are biologically aged under a layer of naturally occurring flor yeast. This strain of the flor yeast varies between different towns and even bodegas, each influencing the wine in a subtly different way. However, flor yeast:

- protects the wine from oxidation

- interacts, causing the wine to evolve

- consumes alcohol, so reducing the alcohol strength of the wine

- reduces residual sugar

- consumes and metabolises glycerin and other elements in the wine, causing an increase in acetaldehydes, the element that gives Fino and Manzanilla sherries their characteristic sharpness.

The need to keep the flor yeast fed with alcohol, glycerin, and nutrients requires young wine to be added to Fino and Manzanilla solera systems.

Flor can be removed by filtration and prevented from reforming by adding more alcohol. Hence, a Fino can be made into an Oroloso by removing the flor to allow the wine to age oxidatively, but you cannot turn an Oroloso into a Fino. After six months in the Solera and prior to the first blending, a proportion of Finos with thinner flor and thus greater oxidisation will be moved to become amontillado-style sherries. Amontillado and Palo Cortado sherries are double-aged, starting as biologically aged finos and then oxidatively.

The maximum average age that a fino can be kept in solara is around ten years. If flor dies, it will become an amontillado.

Oloroso style sherries are aged oxidatively, without a layer of flor yeast being allowed to form due to their being fortified to an alcohol level above which the yeast can withstand. Oxidative ageing:

- results in a wine with a higher alcohol content due to the higher strength of fortification and lack of yeast degradation

- causes the wine to gradually darken in colour due to direct contact with oxygen

- residual sugar, volatile acidity and glycerine levels increase as the wine becomes more concentrated due to evaporation.

Oloroso is the Spanish word for "fragrant", and Oloroso sherries have more intensity than Fino ("fine") sherries.

All sweet styles of sherry (Cream, Moscatel, and Pedro Ximénez) are oxidatively aged.

Before bottling

After solera ageing, the wine may be fortified a second time to standardise its strength, or sweetened with sweet wines or produced from Pedro Ximénez or Moscatel grapes.

Sherry Cocktails

Sherry has been a staple cocktail since the 1800s, appearing in many punch recipes from the period. Today, sherry plays a key role in the world's leading

Lustau

Lustau organises its wines into several range categories (or gamas) beyond just by style: Solera Familiar (Family Solera) - the core, house range Almacenistas